JOHN CARNEY It’s not only difficult for employers to fill open positions in the U.S. economy. It’s increasingly challenging to hold on to workers already on the payroll, especially in traditionally lower-wage jobs.

A record number of people quit their jobs in November, the latest Labor Department survey of hires, openings, and quits showed Tuesday.

The number of quits rose to 4.53 million in November, according to the Labor Department’s Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey. That was a nine percent increase from the prior month and the highest on record. The previous high had been set in September at 4.36 million.

Quits have been at historically elevated levels since passing 3.5 million in March of 2021. On average since the turn of the century, there were 2.7 million quits per month.

Three percent of the total workforce quit in November, matching the record high hit in September.

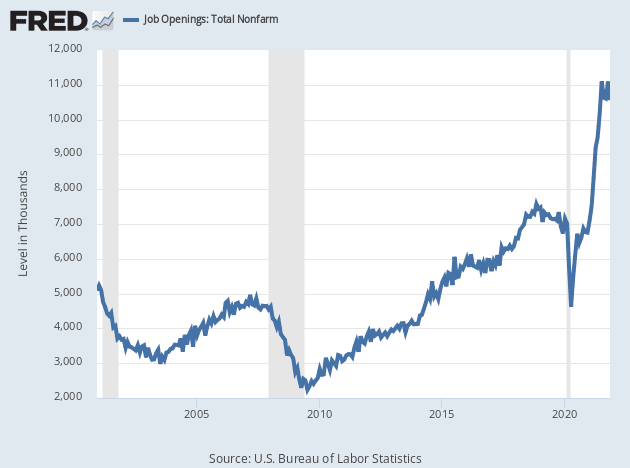

One of the factors driving the high level of quits is the confidence workers have that they can find another job that will pay better or offer better working conditions. The total number job openings in November was 10.56 million. That’s lower than the 11 million consensus forecast and down from 11.09 million in October. But it is extremely high historically speaking and well above the 6.88 million people out of work and looking for employment in November. The prepandemic twenty-first century average number of openings is 4.5 million, so the economy has twice as many available jobs as normal.

While the development of a high level of quits has been labeled the Great Resignation, there is some evidence that a good part of what is driving this is the popping of the cheap labor bubble. The high-powered economy and reduced level of immigration created in the Trump era is now forcing companies and entire sectors of the economy to unwind business models built around the idea that the supply of labor was nearly unlimited, eliminating the need for employers to raise wages or improve conditions to expand payrolls. Now employers are forced to compete for workers.

This can be seen in the elevated rate of hires in the month. The JOLTS report showed that there were 6.7 million hires in the month, which suggests that many of the quitters were not people leaving the workforce but people leaving to work in better jobs.

A gauge of employment from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta shows that people who have switched jobs have seen median wage growth of 4.3 percent while those who have stayed at the same employer have seen wages grow by 3.1 percent. So quitters are prospering.

Leisure and hospitality, one of the sectors most dependent on cheap labor, have seen wage gains of 3.8 percent over the 12-months through November, above the 3.7 percent overall. Trade and transportation workers have seen wages rise 3.9 percent.

The quits level for leisure and hospitality topped one million in November for the first time ever. The rate was 6.4 percent, a full percentage point higher than the October rate and the highest of all sectors of the economy. The sub-category of accommodations and food services saw the level rise to 6.9 percent, also a record.

The Atlanta Fed’s wage tracker also breaks out workers by level of education. Here too the evidence suggests that a good part of what we’re seeing in the current labor market is the fallout from the unwind of cheap labor business models. This year, for the first time ever, wage gains for those with a high school education or less have outpaced those with more education. As of November, the 12-month gain for high school or less-educated workers was 4 percent. Those with Associates Degrees had seen 3.2 percent wage gains. And those with Bachelor’s Degrees had seen wages rise by 3.4 percent.

Last month, Neil Munro reported that the Biden administration is trying to reinflate the cheap labor bubble by importing more workers.

Nationwide, politicians are facing pressure from companies who want the federal government to re-inflate the cheap-labor bubble that it started in 1990. In Washington, that business pressure has added three cheap-labor giveaways buried deep in the pending Build Back Better bill.

Biden’s deputies are trying to re-inflate the cheap-labor bubble. So far, they have imported roughly 1.5 million migrants — both legal immigrants and illegal migrants — during 2021.

Openings fell in manufacturing for both durable goods makers and nondurables, while hires were steady in durables and down only slightly in nondurables. It is too early to tell whether this combination points to coming relief from some supply chain problems or suggests a slowing in growth due to those problems.