Rachel Holliday Smith and Samantha Maldonado, THE CITY

This article was by THE CITY

The city is not just choosing a new mayor in November. This fall, New York voters must also decide on five proposed changes to the state constitution.

Five ballot proposals are up for a vote in the general election on Nov. 2. They include questions on the future of political representation in Albany, environmental protections, easier voter registration and absentee balloting, and how New York’s civil courts function.

The full text of the five proposals are listed on the Board of Elections website and at Ballotpedia, the nonprofit political encyclopedia. But voters who aren’t political mavens may need a bit of context:

Where do these ballot proposals come from?

Unlike California, for example, where citizens can initiate a ballot proposal, New York is one of 24 states where the measures must come from legislators only, not directly from the people.

The five proposals up for consideration in November all came from Albany, where our reps voted for them in both the Assembly and the State Senate before they could arrive on your ballot, noted.

Hasani Gittens/THE CITY

Hasani Gittens/THE CITYBefore getting on the ballot, the proposals must be approved by both houses of the legislature, then voted on again in both chambers after the Senate and Assembly have had one election cycle. Since New York legislator’s terms are two years long, it could take between two and four years to pass a ballot measure.

Then, when it’s ready for voters, the state Board of Elections converts the often dense, legal language passed by the legislature into fairly plain text on the ballot.

“The Board of Elections is not only designing the ballot itself, but they’re writing the question that voters see,” Ryan Byrne, leader of the Ballot Measure Project at Ballotpedia.

That doesn’t necessarily mean the ballot measures are easy to understand.

Ballotpedia tallies how difficult it is to read ballot measures across the country, and this year, New York’s five proposals are at a grade level “14,” on average — meaning two years after high school “halfway through a bachelor’s degree,” Byrne said.

But that’s on the low end, relatively speaking. In Colorado, he said, state ballot measures are at a grade level “32” this year — the equivalent of a doctoral degree and then some.

How likely is it that the proposals will pass?

Statistically speaking, pretty likely. In New York, voters approved 74% of statewide ballot measures between 1985 and 2020, Ballotpedia found.

“Overwhelmingly, they get approved,” said Rachael Fauss, senior research analyst for Reinvent Albany, a government watchdog group.

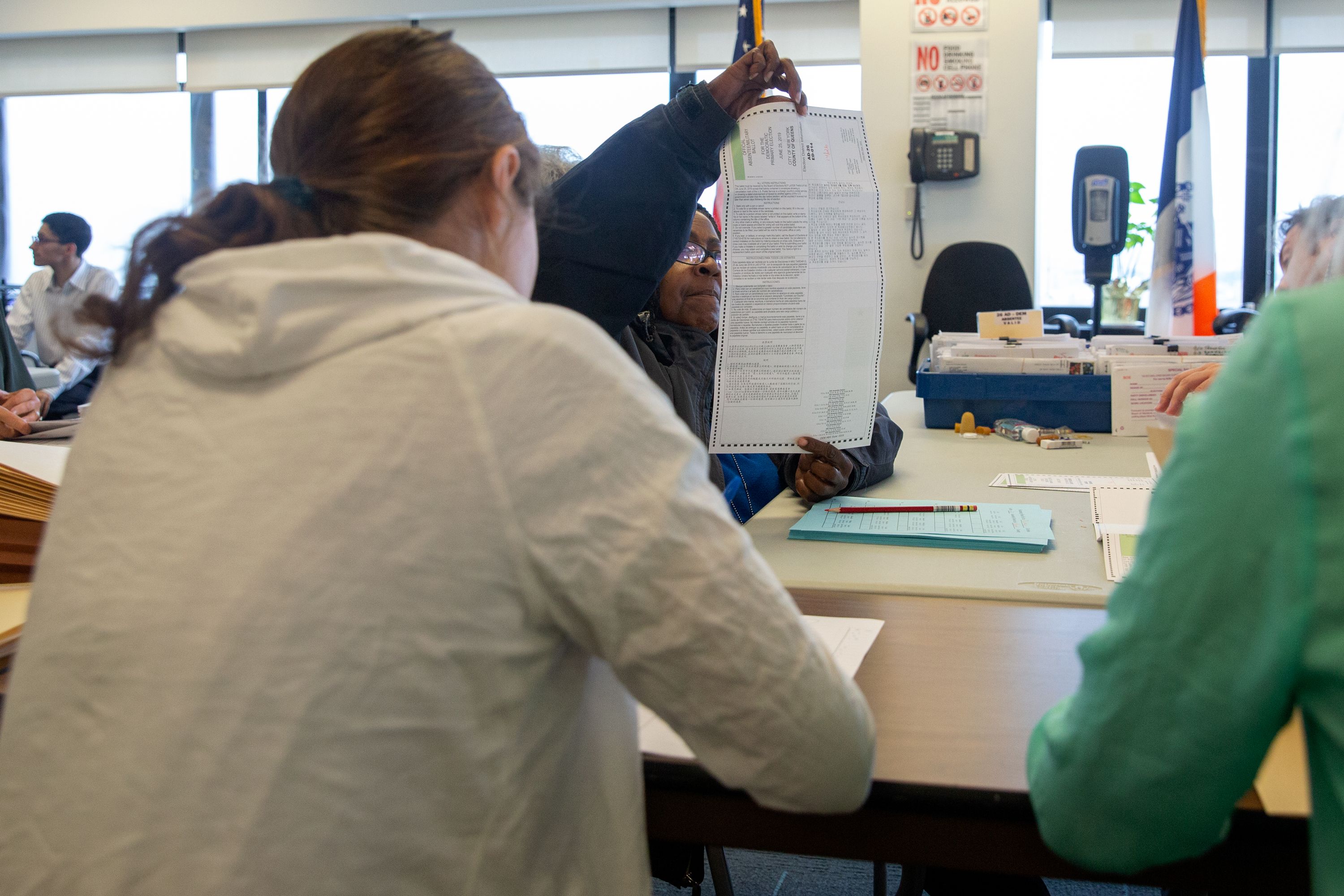

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITYBoard of Elections workers count absentee and affidavit ballots, July 3, 2019.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITYBoard of Elections workers count absentee and affidavit ballots, July 3, 2019.

Ballotpedia found that in odd-numbered election years, proposals in New York have been approved 65% of the time. In even-numbered years, that number goes up to 83%.

Typically, the people who vote on ballot measures are “the people who are paying attention to them, generally,” Fauss said.

Plus, it takes a bit more effort to read and fill out ballot proposals. Often, they’re on a second page.

“A lot of people leave them blank,” Fauss said.

What happens to a ballot proposal after we vote?

New York voters have the final say on ballot measures and, if they’re approved, they’ll go into effect on Jan. 1, 2022.

“The enactment process for state constitutional amendments is the voter. So, voters are essentially acting as that signature or veto,” he said.

If the measure is voted down, it’s scrapped and would have to be reintroduced and passed by the Legislature again to appear on a future ballot.

The Ballot Measures

Proposal 1 — Redistricting

The first ballot proposal is really several questions rolled into one, all on the subject of redistricting.

Redistricting is the process that state lawmakers go through to redraw the boundaries of Congressional and state legislative districts based on the new population numbers reported from the once-a-decade census.

It’s a complicated and important process that will shape political representation at all levels for the next decade.

Proposal 1 asks voters to approve several constitutional changes to the redistricting process. Supporters say the proposal is fundamental to making sure it all gets done on time and with less partisan bias. Detractors, particularly from the Republican Party, say the measure is Democratic scale-tipping that leaves the political minority with less power.

There are more than a dozen individual changes to the constitution wrapped up in Proposal 1, but voters must vote yes or no on them all together. Here are the top changes, according to experts:

- Cap the total number of state senators at 63

- Require that incarcerated people be counted at the address where they lived before going to jail or prison for the purposes of redistricting — not where they are being detained

- Move up the timeline by two weeks for when redistricting plans must be submitted to the legislature

- Change the vote total needed to adopt redistricting plans when one political party controls both legislative houses

The state senator cap is an attempt by Albany lawmakers to prevent future legislators from creating new districts to tip the partisan balance of the legislature.

The measure regarding incarcerated people will ban what’s called “prison gerrymandering” — or counting inmates where they are incarcerated rather than where they lived before going to prison or jail, said Jeff Wice, a New York Law School professor and redistricting expert.

The measure would, on the whole, boost the population of downstate counties, especially in New York City, and take away from the upstate counties where many state prisons are located. State law already includes a ban on prison gerrymandering for state-level political districts, but Proposal 1 would enshrine it in the constitution for Congressional-level redistricting, as well.

Jayne Lipkovich/Shutterstock

Jayne Lipkovich/ShutterstockThe proposal would also stipulate that when one political party controls the Assembly and State Senate — as the Democrats do now in Albany — just a simple majority would be required to approve of the redistricting plans that come from the so-called Independent Redistricting Commission.

Currently, two-thirds of each house must approve redistricting maps if one party controls the Legislature. Democrats in the Senate and Assembly both have a supermajority in their chambers.

Wice supports the proposal and says though there are many important pieces to it, the most crucial may be a seemingly dry calendar change.

To cope with a pandemic-related delay in the release of 2020 Census data and New York’s relatively new June primary date, Proposal 1 would move back the date the Commission must first submit its redistricting maps to the Legislature by two weeks, from Jan. 15 to Jan. 1, 2022. If the Legislature rejects the first plan, the Commission would then have to submit another draft by Jan. 15 instead of the current deadline of Feb. 28, 2022.

For future once-a-decade redistricting processes in 2032, 2042 and so on, Proposal 1 would set the first and second deadlines from the commission on Nov. 15 and Jan. 1, respectively.

This is important to give enough time for the Commission to hammer out the new election districts before candidates must, by state law, start gathering signatures — a process known as petitioning — to get their names on the ballot in those districts. (But state lawmakers can still take matters into their own hands and draw the boundaries themselves if they don’t like what the commission comes up with.)

If voters don’t approve the change and the boundaries aren’t set for election districts before candidates must start petitioning and campaigning, that could mean a messy rush for hopefuls competing in a June primary, Wice said.

“That’s, in part, why this amendment was crafted and put forward,” he said.

But opponents of the proposal — especially those among the state’s Republicans — are pushing back hard. In an interview on the issue with Spectrum News, former U.S. Rep. John Faso described Proposal 1 as “a very cynical maneuver” by the Democrats to “consolidate their power.”

“The true purpose of this entire thing is to eviscerate any ability of the minority party, in this case Republicans, to have a role in the redistricting process,” he said.

Good government groups in the state are split on the measure. New York Common Cause and New York Public Interest Research Group called it an imperfect but necessary change.

The two groups cheered the 63-senator cap, proposed rules for counting incarcerated New Yorkers, timetable changes and other measures while noting “the proposal falls short of the full reforms we believe would provide truly independent [redistricting] commission,” they said in a joint statement earlier this year.

The League of Women Voters of New York State wants voters to reject the proposal. The group said Proposal 1 “would weaken the role of the minority party.”

Want more info? The full text of Proposal 1 can be found here from the state Board of Election, Ballotpedia’s guide on the proposal is here and this deep-dive on the measure from Spectrum News is a great resource for understanding the issues at play.

Proposal 2 — Environmental Rights

The second ballot measure would add a broad new right to the state constitution: “Each person shall have a right to clean air and water, and a healthful environment.”

Sounds simple? That’s by design. Environmental advocates who advocated for this measure wanted the language to be general — to push government officials into “making sure that the environment is given that highest level of recognition and protection,” said Maya K. van Rossum, CEO of the Delaware Riverkeeper Network, a Pennsylvania-based environmental group.

In New York, supporters include the League of Conservation Voters, Environmental Advocates of New York, the Adirondack Mountain Club and the NYC Environmental Justice Alliance.

Similar state amendments have been on the books in Pennsylvania and Montana since the 1970s. Van Rossum says her group and several municipalities used Pennsylvania’s measure in 2013 to successfully block provisions of a law that would have expanded fracking across the state.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITYThe simplicity of the language, however, is a chief concern for those who oppose the ballot measure. They say the new proposal will invite a slew of unnecessary lawsuits.

Michael Giaimo, Northeast region director for the American Petroleum Institute, warned that “as written, the provision could result in extensive and costly litigation as the courts will invariably need to interpret the new constitutional amendment.”

Tom Stebbins, executive director of the Lawsuit Reform Alliance of New York, which opposes the measure, said: “We need public servants to regulate our environmental laws. We don’t need profit-seeking attorneys to litigate our laws.”

But Peter Iwanowicz, executive director of Environmental Advocates of New York, said only those harming the environment have a reason to think negatively.

“If you’re not polluting the air or making water dangerous to drink, then you should not have any problems with this amendment,” he said.

Proposals 3 and 4 — Elections and Voting

The third and fourth ballot measures both aim to change rules to allow easier access to the polls.

Proposal 3 would remove a current constitutional rule that you must register to vote at least 10 days before an election in New York.

That would give the green light for same-day voter registration in New York — if the legislature approves it down the line.

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITY

Ben Fractenberg/THE CITYJordan Pantalone, intergovernmental liaison for New York’s Campaign Finance Board, said the measure will make it easier on the many New Yorkers who don’t tune into politics until the last minute.

“Every election we’re getting messages from voters saying, ‘Hey I want to go vote,’ and it’s five days before the election, so they’re unable to do so,” he said.

If voters approve Proposal 3, the Assembly and State Senate can write a new law explicitly allowing would-be voters to register on Election Day. Democratic leaders in both houses have indicated they plan to do so if the ballot measure goes through.

Similarly, Proposal 4 would nix a state constitutional rule that says voters must have an excuse, or valid reason, to vote with an absentee ballot. If the proposal gets voter approval, it would clear the way for the state Legislature to make no-excuse absentee voting a permanent option.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread voting by absentee ballot was effectively allowed for any New Yorker due to an emergency executive order from then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo. The order said any voter at risk of contracting the virus could legally request an absentee ballot.

Voters took advantage of the option and cast absentee ballots five times as much as they had in previous elections. This ballot measure aims to clear a pathway for doing away with the need for any excuse.

Proposal 5 — Civil Court’s Claim Limit

The fifth ballot proposal seeks to change the monetary limit on claims in the city’s civil court, which is regulated by the state constitution.

Currently, in New York City’s Civil Court, only cases involving claims worth $25,000 or less may be heard. Proposal 5 would lift that limit to $50,000.

Why do this? At the time it was proposed and approved in the Legislature, bill sponsor State Senator Luis Sepulveda cited a need to reduce the caseload in the court system, especially State Supreme Court, which currently takes on any cases involving claims over $25,000.

Sidney Cherubin, a Brooklyn Law School professor and director of legal services at the Brooklyn Volunteer Lawyers Project, supports the amendment as “an attempt to make the judicial system more efficient and to better serve the needs of New Yorkers,” he said.

“It doesn’t solve everything, but it’s a step in the right direction,” he said.

But he stressed that more cases in Civil Court will make a busy court even more bogged down — and, ballot measure aside, lawmakers need to allocate funding and more staff to the court system to make sure it runs smoothly.

If Proposal 5 passes, it will be the first time the claims jurisdiction has changed in Civil Court since 1983. Voters considered a nearly identical ballot measure to increase the claims jurisdiction to $50,000 in 1995, but it was narrowly defeated.

“It may have to do with the fact that this affects New York City and not the rest of the state,” Cherubin said. “So, people don’t care. It doesn’t affect them, so why bother?”

THE CITY is an independent, nonprofit news outlet dedicated to hard-hitting reporting that serves the people of New York.