By Menachem Posner(Chabbad.org)

1. Sukkot Starts on a Full Moon

The Jewish Holiday of Sukkot begins at nightfall before the 15th of the Jewish (lunar) month of Tishrei, when the moon is at its zenith. It continues for another seven days before leading directly into the holiday of Shemini Atzeret/Simchat Torah.

2. Sukkot Is the Holiday of Shelters

Sukkot is Hebrew for “booths” or “shelters.” As the verse states, “Your [ensuing] generations should know that I had the children of Israel live in shelters when I took them out of the land of Egypt.”1

What were these shelters? The Talmud tells us that they were the clouds of glory that encompassed the entire nation during their epic 40-year trek through the Sinai desert.

3. Sukkot Has Three Other Names

Sukkot also has an agricultural connotation, marking the time when farmers in Israel would gather the crops that had been drying in the fields. For this reason, scripture calls it Chag Haasif, “The Festival of Gathering.”2

Sukkot is a joyous holiday—so joyous that the sages called it simply Chag, Hebrew for “Festival.”

In our liturgy, we call it Zeman Simchatenu, “The Time of Our Rejoicing.”

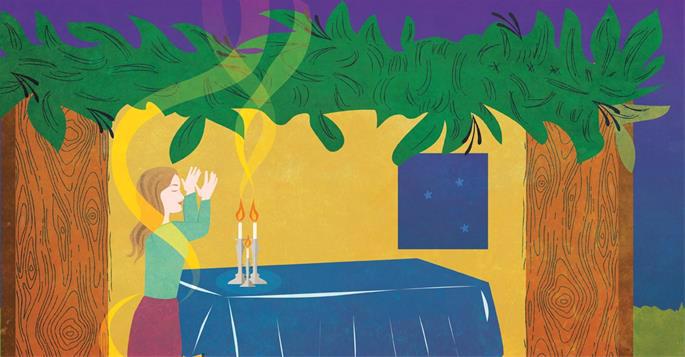

4. The Sukkah Booth Is Covered With Organic Material

For the duration of Sukkot, the sukkah—a structure covered with greenery, bamboo or something else that has been harvested from the ground—becomes our home. The covering is known as sechach. Kosher sechach must have grown from the ground and been harvested. It cannot be the overhang of a nearby tree, for example. Common sechach choices include evergreen branches, cornstalks, palm fronds, bamboo or specially produced mats.

Explore the rules of sukkah construction and their inner meaning

5. The Sukkah Becomes Our Second Home on Sukkot

We eat all meals, study and schmooze (and some even sleep) in the sukkah, where only the flimsy sechach separates us from the wide, open sky.

A sukkah can be erected just about anywhere, provided that it’s under the sky. The Talmud talks about ox-cart sukkahs, boat sukkahs, treetop sukkahs and camelback sukkahs.3 Nowadays there are sukkah mobiles (on pickup trucks) and even pedi-sukkahs.

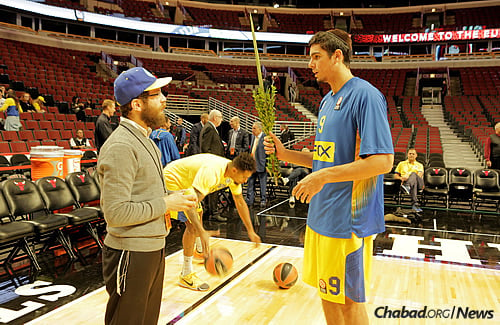

6. The Lulav and Etrog Are Taken (Almost) Every Day of Sukkot

Every day of Sukkot (besides for Shabbat) we take a bundle of greens—made of a lulav (palm frond), three hadasim (myrtles), and two aravot (willows)—along with an etrog (citron). We hold them together, bless G‑d who “sanctified us with His commandments and commanded concerning the taking of the lulav,” and wave them gently in six directions. This is often referred to as the “lulav and etrog” or the arba minim, “four kinds.” (Do you need a set? Contact your local Chabad rabbi, or click here.)

The four kinds are also held and waved during Hallel (“Psalms of Praise” said as part of the holiday morning service), as well as during the Hoshaanot, a daily Sukkot ceremony that involves circling a Torah scroll while chanting prayers for salvation.

7. There Are Special Blessings to Be Said

In addition to the blessing we say before taking the lulav and etrog, whenever you sit down to a meal in the sukkah, you say a blessing that concludes with the words “layshav basukkah,” in which you bless G‑d “Who sanctified us with His commandments and commanded us to dwell in the sukkah.”

The first time you do each mitzvah you make another blessing, Shehecheyanu, which blesses G‑d, Who has “given us life, sustained us, and brought us to this time.”

8. The Last Day Is Hoshana Rabbah

On the seventh day of Sukkot, the bimah (platform in middle of the synagogue) is circled seven times, instead of the one circuit done every day of the holiday thus far. Since the Hoshaanot are repeated again and again, this day is known as Hoshana Rabbah (“The Great Hoshana”). At the end of this once-a-year service, each person beats a bundle of five willows (also known as hoshaanot) against the ground.

On this day, it is customary to have a festive meal in the sukkah that includes challah dipped in honey (the last time for the season) and kreplach, dumplings stuffed with meat.

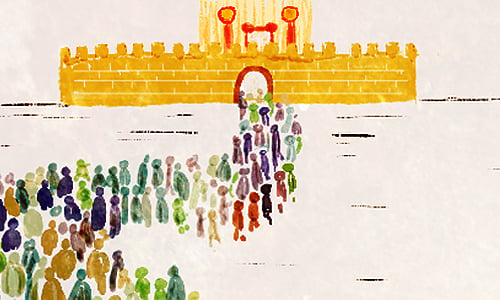

9. Sukkot Was a Pilgrimage Festival

The Torah mandates the Israelites to pilgrimage to the Holy Temple three times a year—Passover, Shavuot, and Sukkot—bringing sacrifices and other donations that they may have promised in the preceding months. Sukkot was the last of the three festivals, and, according to some, it was the final date before the Divine “debts” would be considered overdue.

10. The Joyous Water Drawing Was on Sukkot

During Temple times, the nights of Sukkot were celebrated with extreme joy, to the degree that the sages testified, “Anyone who has not seen the joy of the water drawing, has never seen joy in his life.”4 The celebrations preceded the drawing of water from the shiloach spring, which was then poured into a special hole on the Temple altar.

Priests kindled fires on great lamps, lighting up Jerusalem as if it were the middle of the day. Throughout the night, pious men danced holding torches, scholars juggled, and Levites played music, while the lay people watched with excitement.

Nowadays, many communities hold celebrations on the nights of Sukkot in commemoration of the water-drawing ceremony. The Rebbe encouraged that the dancing spill out into the streets.

11. Spiritual Guests Visit Every Day of Sukkot

According to a mystical tradition found in the Zohar, the “seven shepherds” visit our sukkahs each day of the holiday. Known as ushpizin, the guests are: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Joseph and David.

Some people recite a special text, in which they formally “invite” the ushpizin into their sukkahs.

12. Not All the Days Are the Same

The first two days of Sukkot (just the first day in Israel) are Yom Tov. Like Shabbat, we refrain from many forms of creative labor, travel, etc. The only two exceptions are that some acts of food preparation (such as cooking using a pre-existing flame) and carrying things we need for the holiday are allowed. The prayers are also somewhat longer than usual.

The remaining days of Sukkot are known as chol hamoed, during which travel and other melachot (forbidden acts) are permitted (but strenuous work should be avoided if possible).

13. Sukkot Is Followed by Another Holiday

s://w2.chabad.org/media/images/913/Mkbz9135305.jpg?_i=_n32DD4A5CE5B405756B86D11830CBE5B1" sizes="(min-width: 768px) 685px, 100vw" srcset="https://w2.chabad.org/media/images/913/Mkbz9135305.jpg?_i=_n32DD4A5CE5B405756B86D11830CBE5B1 500w, https://w2.chabad.org/media/images/913/Mkbz9135305.jpg?_i=_n76B3E6A404D908E662A1538A4A879637 480w" alt="Images (from Flash90) were not captured on the holiday." />

s://w2.chabad.org/media/images/913/Mkbz9135305.jpg?_i=_n32DD4A5CE5B405756B86D11830CBE5B1" sizes="(min-width: 768px) 685px, 100vw" srcset="https://w2.chabad.org/media/images/913/Mkbz9135305.jpg?_i=_n32DD4A5CE5B405756B86D11830CBE5B1 500w, https://w2.chabad.org/media/images/913/Mkbz9135305.jpg?_i=_n76B3E6A404D908E662A1538A4A879637 480w" alt="Images (from Flash90) were not captured on the holiday." />Immediately after the seven days of Sukkot, we step into Shemini Atzeret and Simchat Torah. In the Diaspora, this holiday extends for two days; in Israel, it is confined to a single day. Simchat Torah fetes the completion of the annual Torah-reading cycle and the start of the new cycle. It is marked with vigorous singing and dancing in the synagogue. This is the only instance of one Jewish holiday coming directly after another one.