Written by: Ahron Friedberg, M.D., with Sandra Sherman

Reviewed by: TJVNews.com

Just a few weeks ago, the pandemic seemed to be receding. We were back on the street, restaurants were packed. With a sigh of relief, we re-emerged. You could see people’s faces again. If that trajectory had continued, then Through a Screen Darkly: Psychiatric Reflections During the Pandemic would seem like an elegant, but past-tense reminder of what we’d just been through. But now, with growing concern over the Delta variant, our fear of breakthrough infections and the likelihood of a third-shot booster, Screen reads like current events. Its stories of the pandemic’s impact on our neighbors’ mental health still apply, today, to most of us, maybe all of us. And the stories are riveting.

Ahron Friedberg, M.D., is a Manhattan psychiatrist who treated patients that were upended, destabilized, and in any number of ways deeply troubled by the pandemic. Screen collects stories of their emotional travail. Amidst all the statistics by which we will measure this pandemic – how many sick, how many dead or jobless or displaced – this book is the first to render what occurred on a profoundly human scale. How did these people cope? How did they develop resilience to keep on keeping on when their lives seemed suddenly out of kilter?

Friedberg answers these questions, recounting the experience of ER doctors on the verge of giving up; teachers whose students read menace into American classics; science fiction writers unable to imagine a future; executives unsure that their children will love them now that they’ve lost their jobs. The stories are kaleidoscopic variations on stress, anxiety, and pain.

Jews are no strangers to pain. As Friedberg remarks in examining the teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov (1772-1819), “Nineteenth century Jews had a talent for describing impending disaster.”

Screen reminds us of our fears. In one story, “The Rabbi and the Pandemic,” Friedberg cites a saying by Rabbi Nachman: “When a person must cross an exceedingly narrow bridge, the general principle and the essential thing is not to frighten yourself at all.” Nachman makes us responsible for our own fear – we are its perpetrators, and hence we must control it. As Friedberg frames it:

In Nachman’s sense, fear is like the virus. It cannot replicate outside

human beings but, once inside, humans become its agent. Nachman is the

great epidemiologist of fear: his warning is that we not allow ourselves to be

complicit in allowing fear to grow.

The Jewish elements of Screen carry an outsize import. Screen brings this old Hasid into our own time.

Friedberg describes how two of his patients, deeply afraid of venturing out, manage to get a grip on fear and find the means to keep living. One goes for a walk after months indoors. Another goes running, even though members of his race were recently assaulted. These people literally put one foot in front of another, traversing Nachman’s “narrow bridge” while not looking down. They did not allow themselves to proliferate fears that, like the virus, will multiply if we give it a favorable environment.

Friedberg observes that Nachman achieves a balance between Jewish millenarianism – the belief in a better world to come – and finding hope in the present:

I like the idea of a bridge in the world. We are not crossing to a

better world, but learning to traverse the troubles in this one. We are

making up our minds to traverse them. My patients put one foot in front

of another – and they are still here.

Screen is full of this kind of practical wisdom. Friedberg is deeply reflective. He draws on philosophy, poetry, art, and even the history of previous plagues to fashion a perspective permeated by the pandemic but, simultaneously, vibrating with a kind of timelessness. Nachman would feel right at home.

In one of the final stories, “In the Light of Eternity,” Friedberg describes the torment of a rabbi who, perhaps out of zeal to keep ritual alive, exposed some mourners to the virus. Some got very sick. The rabbi is remorseful. “This is magical thinking, not religion,” he laments. He keeps encountering death and suffering, and feels powerless to help. When he can no longer hold services, he feels diminished, like “a rabbi whose congregation is a mini-Diaspora.” Friedberg wonders how he can help:

My problem is how to deal with someone whose existence is so

consumed with others’ grief that his own grief becomes overwhelming.

How, especially, do you help someone see that they’re doing the best

they can when the grief all around them keeps escaping their capacity

to address it? All I could say is that we’re all in this together, and that

no person can be expected to bear more than their fair share of the burden.

The story zeroes in on the fundamental predicament of being a rabbi in parlous times – not all of them can be Nachmans, steadily keeping on.

Rabbis (surely, the one in the story) pray that people will hold onto their faith and view their situation in the light of eternity. We are just passing through. Stuff happens. It will all work out – whether in life or death. But how can you carry on with that job when people are living day to day, trying to hold it all together before it all flies apart in a million directions?

Eternity, yes, but not only. Faith can be a source of strength, a refuge, a resource that, at least for moments, saves us from drowning in pain and fear. The rabbi of Screen was unsure whether to include himself among the comforters or those needing comfort. His ambivalence is so classically Jewish, a ready acknowledgment that suffering comes to the best of us, even as we risk complicity with it.

It is still way too early for the Jewish experience of COVID-19 to be fully parsed, but Screen makes a riveting start. Of course, Jews have no monopoly on suffering, but they understand it as an element that structures their sensibility. Friedberg captures this understanding, and goes on record with it. Moreover, while not explicitly saying so in most of the stories he tells, Friedberg situates his patients in a world overwhelmed by suffering. His professional training, as well as his personal identity, allow him to help these people empathetically.

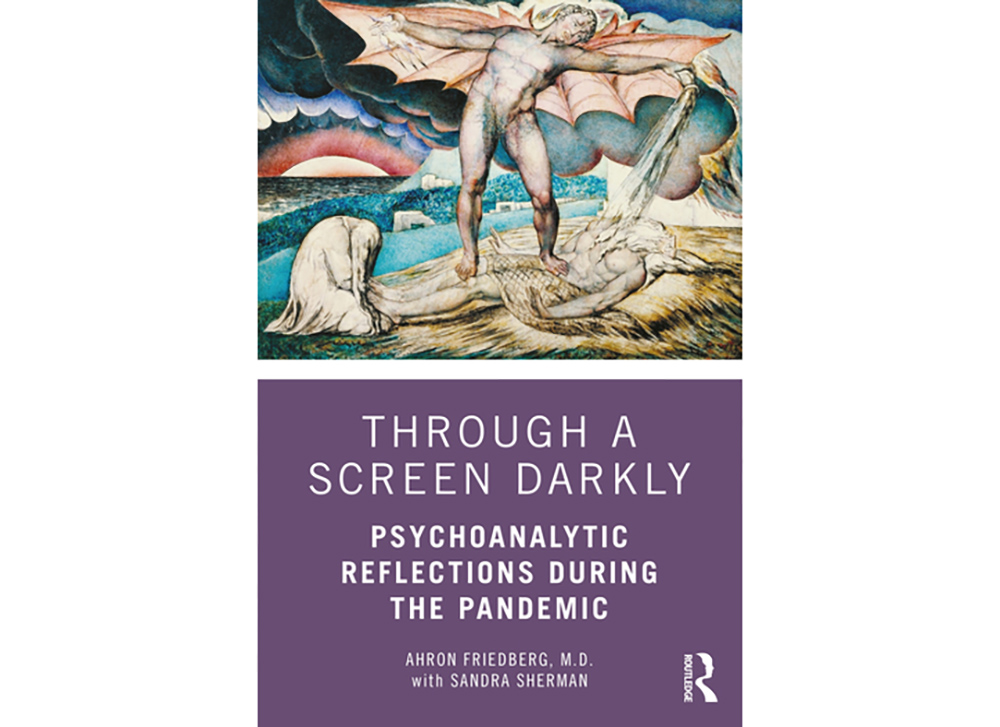

Screen is structured in four phases, starting with the initial, overwhelming onslaught of the pandemic early last year, through a tentative emergence, an adjustment to a new type of normal and, finally, to a period where life offers fewer choices. The periods bleed into each other, more like our own subjective responses than actual chronological distinctions. The effect allows us to feel that we are making progress even while anything can still happen. It is precisely on the mark, given how we feel right now. The images – mostly drawn from medieval and Renaissance texts – reinforce the sense of how time never just marches in one unbendable direction.

If you want to think about the pandemic as a person in this still very uncertain world and, perhaps, even as a Jew, then Screen is the place to start.