By: Meyer Harroch

Most Americans know of Oskar Schindler, the German businessman who saved more than 1,200 lives during the Holocaust, by hiring Jews to work in his factories and fought Nazi efforts to remove them. But not so many people know about Chiune Sugihara, the Japanese diplomat who disobeyed his government’s orders and issued visas that allowed 6,000 Jews to escape from Nazi-occupied territories via Japan. His courage and bravery are now praised by thousands of Jews and non-Jews worldwide, and he has been recognized as one of the Righteous among the Nations at Jerusalem’s Yad Vashem Holocaust memorial. The Sugihara Story is a particularly powerful one.

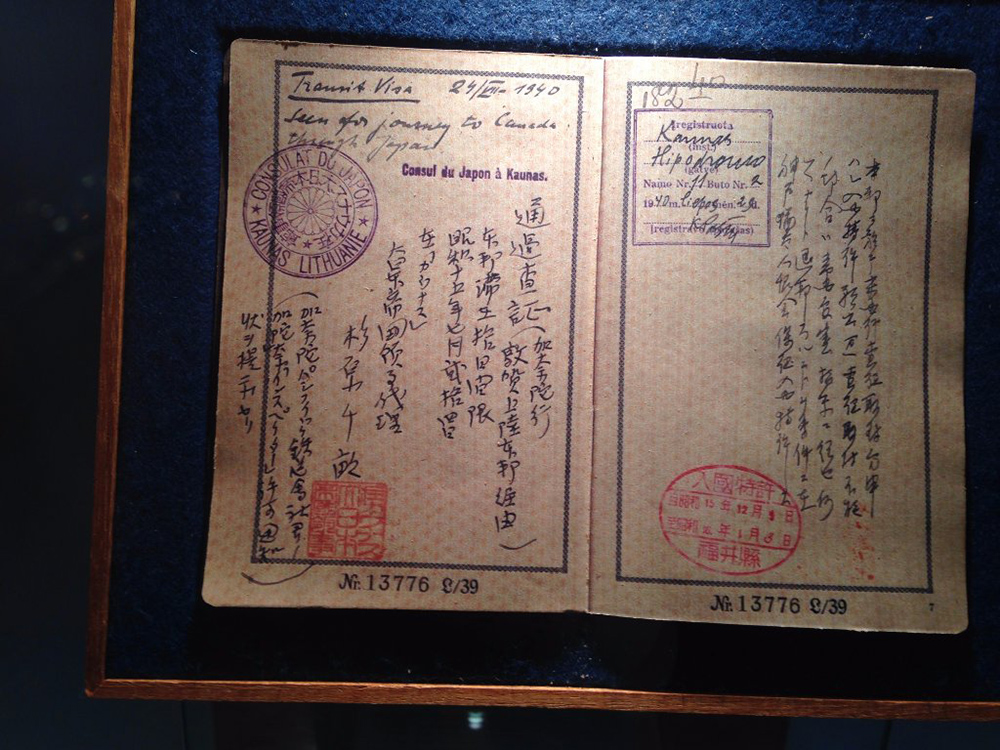

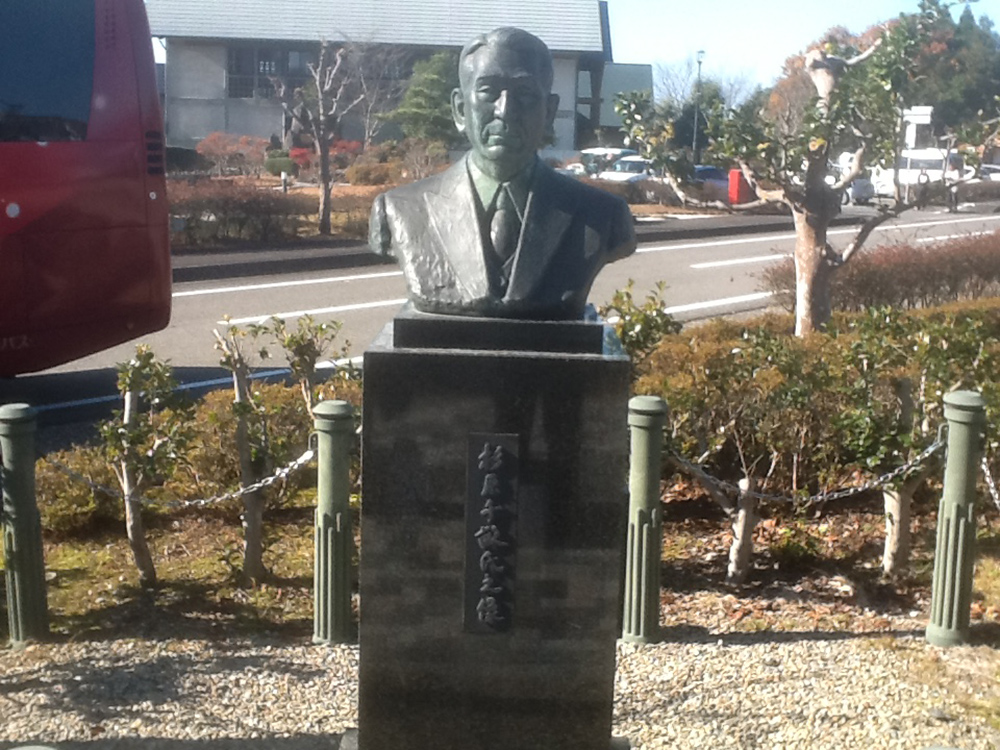

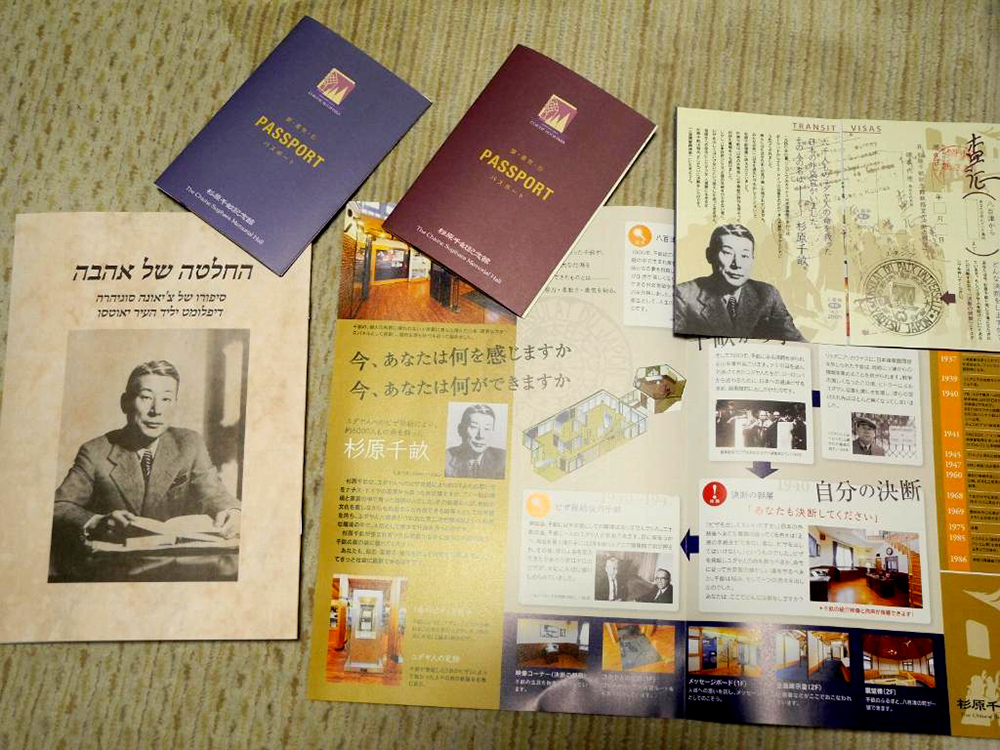

I recently visited Japan’s Gifu Prefecture and the town of Yaotsu, where residents built the Memorial Hall and the Hill of Humanity Park to honor Chiune Sugihara. In the Gifu Prefecture, they have preserved an original document, a passport bearing a Curaçao visa together with a Sugihara visa, which was donated by a survivor named Sylvia Smoller; a replica is exhibited in this Hall. Nearby in Jindounooka Park, whose name means “Hill of Humanity,” a bust of Chiune Sugihara is displayed.

The definition of a “hero” — someone who is admired or idealized for his courage and achievements and sacrifices his career, future, family, and possibly one’s life — is synonymous with Chiune Sugihara. For Sugihara, it would be wrong to willfully ignore the plight of the refugees in the interest of protecting himself or his family, even at a cost to his own safety. To refuse the refugees signed visas would, in effect, be the same as offering them signed death certificates. In deciding between saving his loved ones versus hundreds of strangers, Sugihara chose the latter, in turn saving thousands of Jewish refugees.

Sugihara’s fascinating and incredible life story all started in March 1939, as Europe stood on the brink of World War II. Sugihara, who was appointed to open a Consulate in Kaunas, Lithuania, had barely settled into his new post when the German army invaded Poland. A wave of 15,000 Jewish refugees streamed into Lithuania, bringing terrifying stories of German atrocities.

Caught between the Nazis and the Soviets, they were desperately seeking ways to emigrate; the Soviets only allowed people to pass through Russia if they had a transit visa, issued by Japan, so obtaining a Japanese visa became a matter of life and death. When Lithuania was annexed to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1940, all foreign diplomats were asked to leave Kaunas and the Jewish delegation came to Sugihara with a desperate request: as it had become impossible to obtain immigration visas to go anywhere, the only alternative was Curacao – a Dutch colony – that required no entry visas; Japanese transit visas were necessary in order to obtain permission to cross to the Soviet Union, to reach the port of Vladivostok, from which the Jews could sail west.

Facing all these women, children, and the elderly with pleading eyes made Sugihara feel helpless; he had no authority to issue visas without permission from the Foreign Ministry in Tokyo. Three times he wired his government requesting permission, and all three times he was denied.

Confronted by the plight of the refugees that camped outside his house in hope of assistance, Sugihara defied his government’s orders and endangered himself and his family by hand-writing and issuing hundreds of visas to these Jewish refugees. He was guided by the strength of his morality, and issued these transit visas for 29 days, as he sat for endless hours composing them. Hour after hour, day after day, he wrote and signed 300 visas a day all written entirely by hand and by the time he had to leave Kaunas, thousands of Jews received these visas. But even as Sugihara’s train was about to leave the city, he kept writing visas from his open window. When the train began moving, he gave the visa stamp to a refugee to continue the job. “We will never forget you.” Those were the last words he heard from the refugees. As Sugihara yelled out, “Please forgive me. I cannot write anymore. I wish you the best.”

The residents at the port of Tsuruga warmly welcomed the sudden appearance of a large number of Jewish refugees and carried out a wide variety of actions in support, including providing food and opening public baths just for them. Without such cooperation, thousands of Jewish refugees would not possibly have been sent safely to their final destination, the last stop on their journey to freedom.

It should be also pointed out that the credit for saving these refugees should also be shared with those who aided him, that is, two other men of conscience: Jan Zwartendijk, acting Dutch consul in Lithuania; and L.P.J. de Decker, Dutch ambassador to Latvia, both of who took risks at least as great as Sugihara had, as their country had been occupied by Germany since May 1940. Zwartendijk and de Decker acceded to granting of entry visas to Curacao, the Dutch colony in the Caribbean, without taking the necessary steps to get them authorized on the other end. It was a similar scenario, albeit on a smaller scale, as with Sugihara.

Being a humble and a modest man, Sugihara never mentioned his wartime deeds to anyone, and the world knew little of him until almost 30 years later, in 1968, when Joshua Nishri, the Economic Attache to the Israeli Embassy in Tokyo, located him in Tokyo with one of his survivors. The reunion was most significant for Sugihara, since — after all these years — he had not known whether the visas he signed had actually aided any refugees in fleeing Lithuania. His knowledge that so many people made it to safety brought tears of joy to Sugihara’s eyes, and he was overwhelmed with satisfaction and happiness and with no regrets. Even if only one life had been saved, he felt that all of his hardships would have been worth it. As it is quoted in the Talmud, “Whoever saves a life, it is considered as if he saved an entire world.”

Despite all the publicity given to him in Israel and other nations, he remained virtually unknown in his home country. It was only when a large international Jewish delegation attended his funeral, that his own people discovered his great altruistic deeds. In 1985, Sugihara was the only Japanese person to be awarded the “Righteous Among the Nations”, a title by Yad Vashem on behalf of Israel and the Jewish people, an honorary title given to non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the Holocaust. A monument was erected on a hill in Jerusalem, a cedar grove was planted in Sugihara’s name at Yad Vashem, and a park in Jerusalem was named in his honor. A street in Netanya, Israel was named after Sugihara in June 2016, in a ceremony attended by one of Sugihara’s sons, Nobuki. With Sugihara`s visas, as many as 6,000 refugees were able to flee, making their way to Japan, China, and numerous other countries in safety and known as “Sugihara Survivors”. Now he is considered a hero in Japan, and the refugees he saved have more than 40,000 descendants.

As the governor of Gifu prefecture, Mr. Hajime Furuta explained that in the last few years, the region has seen an increase of foreign tourists, especially those interested in learning about Sugihara. Many tourists also visit and stay at various world heritage towns such as Takayama and Shirakawa-go.

According to Mr. Ken Takashima of the Yaotsu Town Promotion Office, there are over 15,000 Israeli and Jewish tourists from all over the world visiting the Gifu area, in particular, “the Sugihara memorial places.” It was also noted by Mr. Hiroshi Matsumodo, President of JTB (Japan Travel Bureau), that “last year the Gifu Prefecture and JTB formed an agreement in working together not only to honor Sugihara but to share his legacy to the rest of the word and to expand our effort to increase tourism in the Gifu prefecture for the Chiune Sugihara route “Tourism of Humanity.” As part of this effort, they have opened an information center in New York City and Los Angeles.

To conclude, Sugihara wrote in his 1983 memoir, “To be perfectly honest, I am convinced to this day that I took that path of action faithfully, putting my job on the line, without fear or trepidation in my heart.” And perhaps the following words were the most eloquent on his contribution to humanity: “I took it upon myself to save (the refugees). If I was to be punished for this, there was nothing I could do about it. It was my personal conviction to do it as a human being.” Now, Gifu officials are confident and pursuing its placement on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register for the materials and documents related to the vast number of visas he had issued. Certainly, his actions should not just be left as records, but preserved as memory and to perpetuate his legacy. One can only hope that the story of Japan’s admirable diplomat, in due time, will reach all corners of the world.

(New York Jewish Travel Guide)