DEBORAH FINEBLUM(JNS)

Why is Tisha B’Av the saddest day of the Jewish year?

Eerily, not only were both of the holy temples in Jerusalem destroyed on the ninth day of the Hebrew month of Av (the first one, built by King Solomon, was demolished by the Babylonians in 586 BCE, and the second, a gift of King Herod, by the Romans in 70 C.E.), but a host of other tragic events also befell the Jewish people on that date.

Fast-forward to 9 Av 133 C.E., when the Bar Kochba revolt against the Romans ended in bloody defeat and the Temple Mount was plowed over one year later—to the day. In 1290, England expelled its Jews on this date and Spain followed suit in 1492; Germany attacked Russia on ninth of Av in 1914, marking the beginning of World War I, and on the same date in 1941, Heinrich Himmler’s SS was given approval from the Nazi Party to execute the “Final Solution” destined to take the lives of nearly a third of the world’s Jews.

Taken together, these painful events explain the mourning traditions of Tisha B’Av (which this year begins at nightfall on Saturday, July 17, and extends until sundown on Sunday evening). Chief among them: fasting; sitting on the floor or low chairs until midday and eschewing marital relations; listening to music; bathing; swimming; wearing leather shoes; and taking pleasure trips. In addition, after the sun sets and the holiday begins, Jews the world over (usually in synagogue) read Eichah, the book of Lamentations, bewailing the destruction of Jerusalem and the First Temple.

Unfortunately, Jewish grief is not limited to the ancient past; last year’s calendar was littered with tragedy. All too fresh are the grisly deaths of 45 worshippers, many of them children, at the annual Lag B’Omer celebration in Meron, Israel, in addition to last month’s collapse of an apartment building in the predominantly Jewish neighborhood of Surfside, Fla., north of Miami, killing nearly 200 people inside; as well as the destruction from the 4,000-plus missiles launched into Israel by Hamas in Gaza that turned into a violent 11-day conflict in May.

Not to mention the countless thousands of Jews lost in COVID’s merciless revolving door; a number estimated to be well over the national averages because Jewish communities in both North America and Israel tend to be situated in dense population centers, communities that suffered the highest per-capita infection rates.

In one 24-hour period in January, the Jewish people also lost three prominent leaders: Rabbi Dr. Abraham Twerski, a scholar and psychiatrist best known for his 60 books and chain of addiction treatment centers; Rabbi Dovid Soloveitchik, scion of the Brisk dynasty and head of its yeshivah; and Rabbi Yitzchok Scheiner, longtime head of the Kaminetz yeshivah.

Such losses remind Rabbi David Stav, founder and chairman of the Tzohar Rabbinic Organization, a religious Zionist group dedicated to connecting religious and secular Jews, of one of the kinot—poems read on Tisha B’Av—that tells of the 10 holy sages murdered by the Romans 2,000 years ago.

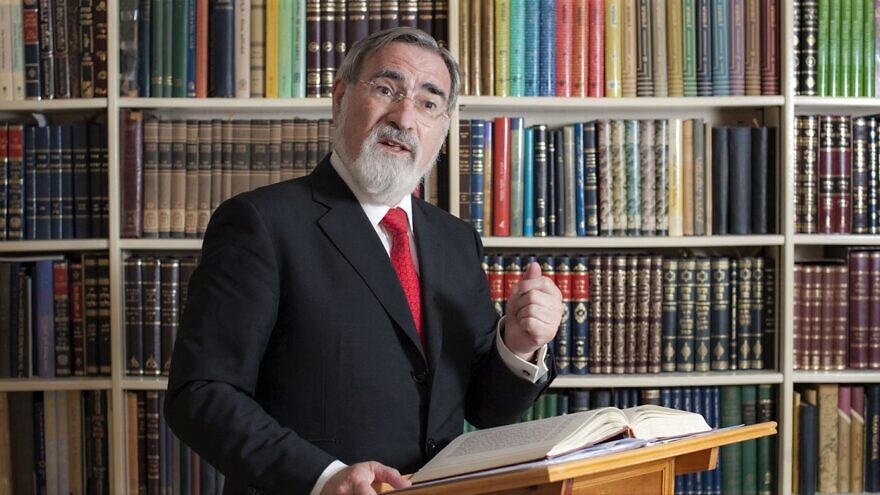

“It says that the loss of righteous people is equal to the loss of the two Temples,” he explains. This past year, the Jewish world lost so many of its leaders, he points out, including Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz and Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, “two of the most powerful speakers for the Jewish people. We lost more of our best and brightest than any other year in the last decade.”

Add to the list the passing of longtime Yeshiva University president and Jewish educator Norman Lamm, who often spoke about reconnecting a divided community.

‘We think it brought us together’

But as much as these losses brought the Jewish people together in shared grief—and a groundswell of caring, including untold numbers of volunteers delivering groceries, medication and other necessities to housebound seniors or those most susceptible to getting sick—COVID itself also emerged as a divisive issue between Jews. Many were critical of their more traditional cousins who live in concentrated communities and whose attendance at synagogues and yeshivahs—and funerals, too—often pushed the limits of lockdowns and regulations.

“On Tisha B’Av, when we recall that we lost the Second Temple because of causeless hatred between Jews,” says Rabbi Binny Freedman, rosh yeshivah of Orayta in Jerusalem, “we have to think of the year-and-a-half when we were isolated and separated physically, when we were masked and socially distant. We were afraid of catching the illness from other people, but there was also something unhealthy about the fact that we were forced into being so distant from each other.”

Another divisive force was social media, the rabbi adds. “We think it brought us together, but consider the rancor on Facebook and the fact that when everyone wishes each other happy birthday online, we don’t even pick up the phone anymore for a personal greeting anymore.”

‘Part of our crying has to be for divisiveness’

At least equally alienating has been the year’s political split between liberal and conservative Jews, and those on the left and right in Israel. Exacerbated by the fractious presidential race in the United States, the divide split families and friends alike, often expressed in volleys of less than civil and highly public social-media posts.

Indeed, the biggest loss of the year, says Stav, is that of “kindness and respect between Jews.” Though he insists that airing some disagreement of opinion is healthy, “when we begin calling each other names, which characterizes this last year far too much, as we mourn the loss of the temples, it’s not just 2,000 years ago but the tragedy that still exists among us, and it’s caused by the same internal hatred that caused it then.”

“Part of our crying has to be for the divisiveness which caused many friendships and even families to rip open this past year,” says Rabbi Shlomo Katz, spiritual leader of the Shirat David community in Efrat, recording artist and author of The Soul of Jerusalem, among other titles. “Our tradition teaches us that the only way to heal it is to have the self-control to minimize our ego and remember that relationships should never be based on what a person believes politically,” he adds. “Only when we deeply understand that can we begin to repair the rift, build trust and have the conversation that we really want to have with this person.”

Or, as Stav puts it, “We can begin to heal the anger and hurt between Jews by extending a hand to shake, really listening to the other’s opinions and trying to understand with an open mind, basically to give them respect—no matter how they voted.”

‘We need to rebuild that oneness’

But unity (achdut in Hebrew,) may be getting a helping hand from an unlikely source: the very people who hate us. Indeed, this year Tisha B’Av arrives at a time when the Jewish people are again beset by a common enemy: anti-Semitism.

In the fight against perhaps the world’s oldest scourge, one potent weapon is Jewish unity, insists Freedman. “When Jews came together in the Beit Hamikdash, the holy Temple, there were no Reform or Conservative or Orthodox—only the overwhelming feeling of God’s presence, an awe so powerful that we could put aside our petty differences,” he says. “Now, Tisha B’Av is coming to remind us that even without the Temple, we need to rebuild that oneness. We need to find a way to draw closer to each other.”

There is also no better time than Tisha B’Av to count blessings to counterbalance the grief, including the existence of the State of Israel, something most Jews could only dream of a century ago.

“With each passing year, the commemoration of Tisha B’Av shifts away a little farther away from mourning the Great Destructions to the realization that the many generations of mourners before us generated the recovery of Zion,” says Ruth Wisse, retired Harvard University professor and author of Jews and Power. “Theirs was no mere bewailing the past, but testimony to how precious the resumption of Jewish religious and political autonomy would someday be.”

“Our mourning includes responsibility for all that they foretold,” adds Wisse, now distinguished senior fellow at the New York-based think-tank the Tikvah Fund. “And all that has come to pass.”