The challenges, difficulties and triumphs of English-speaking women living in Israel are told in their own words in a new book.

By: Rochel Sylvetsky

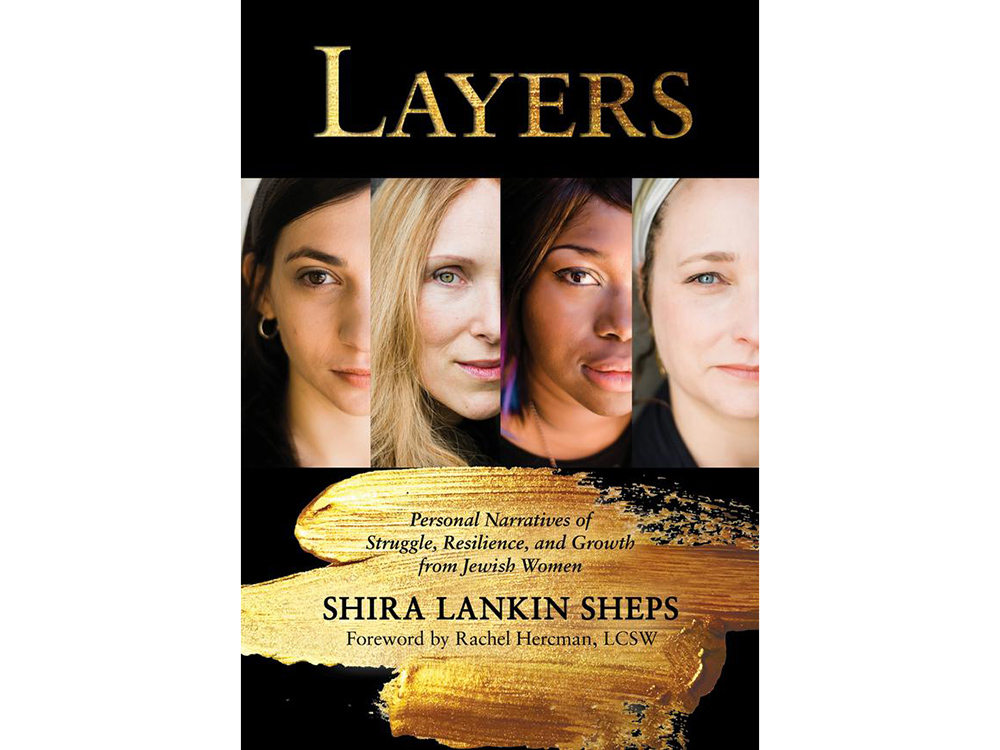

Reviewing the book Layers, Personal Narratives of Struggle, Resilience and Growth from Jewish Women, compiled by Shira Lankin Sheps (Toby Press), a book with 30 personal autobiographic stories of women who have overcome difficulties or are in the midst of a lifelong effort to do so, seemed out of sync to me at first.

After all, 2021 is a traumatic year for everyone, first due to the Corona pandemic, the restrictions accompanying it, the pain of those who fell ill and the losses of loved ones who succumbed to the virus. The Jewish world was traumatized once again by the Lag Ba’Omer tragedy in Meron which left 45 celebrants dead and 45 families and their many friends bereft and by the tragedy in Givat Ze’ev’s Karlin-Stoliner synagogue. In May, barrages of lethal rockets launched at Israeli civilians by Hamas and the Islamic Jihad led to Operation Guardian of the Walls in Gaza, with the country’s citizens rushing to shelters at all hours. Concomitantly, the Israeli Arab uprising, a violent, hate-filled series of pogroms in cities where coexistence was thought successful, traumatized the idealistic young families who had moved to mixed population cities, and the Israeli public, and may have destroyed any hopes of peace. A steep rise in anti-Semitic incidents in the West shocked Jews the world over

(Ed. Note:The Arab riots in Israel were eerily reminiscent of the 1929 Hevron massacre before the establishment of the State of Israel when Arabs who had been peaceful neighbors of Jews for years pillaged, raped and murdered unarmed innocents. The difference? The presence of determined Jewish self-defense in 2021 – not the police, whose inaction was also eerily reminiscent of the British Mandate police in 1929 – but Jews who came from all over Israel of their own volition to defend their brothers, and Jewish builders who joined forces, came and rebuilt burnt synagogues.)

If the number of articles and columns already posted about the above subjects are an indication, it won’t take long before a plethora of books are published about Meron, the Guardian of the Walls operation, the Arab riots, Western anti-Semitism. Among them, there will be no shortage of personal stories of those who suffered and lived through these events as well as those who, sadly, did not survive them.

However, just a few minutes of reading Layers suffice to realize that this book contains intensely personal stories, relevant because individual challenges arise and continue to demand attention independent of local or international events.

Shira Lankin Sheps’ internet site The Layers Project Magazine, where women were welcomed to tell their stories, was the catalyst for the book, acting as an incubator of sorts.

This type of book seems a product of the internet age in which the new norm is a propensity, probably traceable to social media, for so many members of this generation to talk about themselves frequently, openly and more easily than those before them, who believed in a stiff upper lip. Some say it is a product of the emphasis this “me” generation places on itself rather than on ideology and ideas, but that is not necessarily the case when real suffering is revealed, as in this book, where it is more likely catharsis and also represents the hope that the stories can help others cope.

Nevertheless, the tendency to publicize the lurid details of one’s problems is, how shall I say it? – revealing. The positive aspect of it is that women feel free enough to do so – and most of them come across as unbelievably brave as their predecessors, mostly unsung women throughout history, have been.

Sheps admits that gathering the stories for this book was harder for her than posting individual stories because she travelled around the country to get to know the writers personally. It is also much harder to read in book form in contrast to scanning individual posts on the site. I suggest that readers do as I did–read it in stages, to avoid the cumulative depressing influence of so many sad stories. It makes no difference that the point of the book is how each one of these women coped and that the endings are mostly upbeat, because the reader has to live through the saga each woman endures until she reaches that stage. Sheps writes: “Pain and joy are not mutually exclusive. I tell the stories because within them is beauty…” Still, it is a cumulatively wrenching read.

Sheps is not a Hebrew speaker, so she chose women who speak English well. That makes it easier for the Anglo reader to identify, but It is also striking that while the women all live in Israel, there is not one story about an IDF widow or orphan.

The short and terse sentences the editing seems to favor – perhaps considered more realistic–make for a choppy style that causes the beginnings of the stories to seem repetitive, although they are not. On the positive side, the fact that the women wrote their own stories makes the book credible, leads to the hope that writing helped them process the heartache, and certainly adds to reader involvement.

Some of the narratives open up areas with which many of us are not familiar, and that is mostly, but not necessarily always, a good thing. Many of the stories are inspiring – I found the story of the Holocaust survivor, the Ethiopian immigrant and the IDF officer to be especially so. The stories of the woman caring for a husband with MS, the woman battling cancer, the woman whose mother was murdered by terrorists on the road to Efrat (I remember that tragedy well), the feelings of a convert and of the women dealing with infertility, the caring perseverance of sisters who fought bureaucracy to care for their challenged brother–elicited my respect and admiration for their strength in facing what life handed to them. In contrast, I found several of the stories strange and somewhat incomprehensible – in one or two of these, I could not tell whether the women telling them were Jewish, and I think the book would be better without them.

There are stories centered on the challenges of haredi women who could not have as many children as they hoped, opening my eyes to how important having a large family is in that sector. There are also several instances of weight problem issues, possibly a more prevalent problem than I am aware of, which may be of interest to readers. Some of the stories show what love is all about and some show what teamwork can accomplish, some exhibit a profound love of the Jewish State and many a deep attachment to Judaism and Torah.

As is often the case today, each chapter has a self help appendix, with questions and suggestions for discussion at the end of each story, described as “reflection spaces and exercises for guided reading, contemplation, and discussion that create an experience that is both personal and thought provoking.” It’s possible I do not relate to the self improvement efforts because of the large numbers of self help books on the market, literally a trend with no end, and I did not read them after a glance at the first few. Truth to tell, the book itself is a learning process and provides food for thought, introspection, identification, and self-analysis without the artificial addition – and when you read the book, see if you agree.

This article originally appeared on www.israelnationalnews.com

Rochel Sylvetsky made aliya to Israel with her husband and young family in 1971, coordinated Mathematics at Jerusalem’s Ulpenat Horev, worked in math curriculum planning at Hebrew U. and as academic coordinator at Touro College Graduate School in Jerusalem. She served as Chairperson of Emunah Israel and was CEO of Kfar Hassidim Youth Village. Upon her retirement, Arutz Sheva asked her to be managing editor of their English site, a position she filled for several years before becoming Senior Consultant and Op-ed and Judaism editor. She serves on the Boards of Orot Yisrael College and the Knesset Channel. Her articles and book reviews have appeared in various English and Hebrew publications.