Ryan McMaken(MISES)

During Tuesday’s presidential debate, former vice president Biden attempted to paint Donald Trump as the bad-on-crime candidate when he claimed that crime had gone down during the Obama administration but increased during Trump’s term.

Whether or not this is a plausible claim depends on how one looks at the data. And given that law enforcement and criminal prosecutions for street crime are generally a state and local matter, it’s unclear why any president ought to be awarded blame or plaudits for short-term trends that occur during his administration.

Overall, however, it does look like homicides—which tend to be a good indicator of general crime trends—are indeed rising this year. While many factors are likely at play, we may be seeing yet another side effect of the stay-at-home orders and resulting social fragmentation that have come to be part of the landscape of 2020. As workplaces were closed down, joblessness rose, and community organizations were shuttered, city and state governments may have been paving the way for more social conflict and crime.

Homicide in 2019

In assessing the larger context, we can turn to this week’s new report released by the FBI on 2019’s crime and homicides, and we have partial data from 2020 as well.

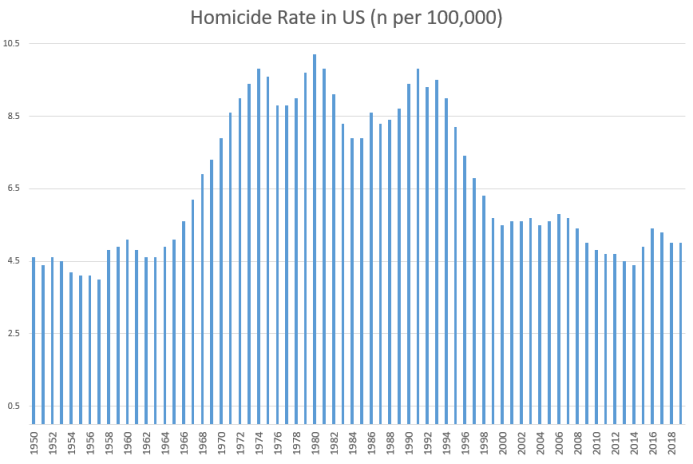

There is no doubt that 2019’s homicides were up slightly from where they were six years earlier. Back in 2014, homicides in the United States hit a 51-year low, falling to 4.4 victims per hundred thousand residents. That is, homicides that year fell to the lowest rate seen since the postwar days, when homicides were exceptionally low and at some of the lowest rates seen since the eighteenth century.

Since then, homicide rates have risen but have remained well below the high rates the nation experienced from the 1970s into the 1990s.

Nationwide from 2018 to 2019, the homicide rate remained unchanged at five victims per hundred thousand population. (That’’ only about half the rate of homicides we saw during the late seventies and early nineties, when homicides hovered around ten per hundred thousand.)

But homicides have certainly not been evenly distributed. Total homicides in recent years have been largely driven by high levels in a relatively small number of big cities like Baltimore, Memphis, and Chicago.

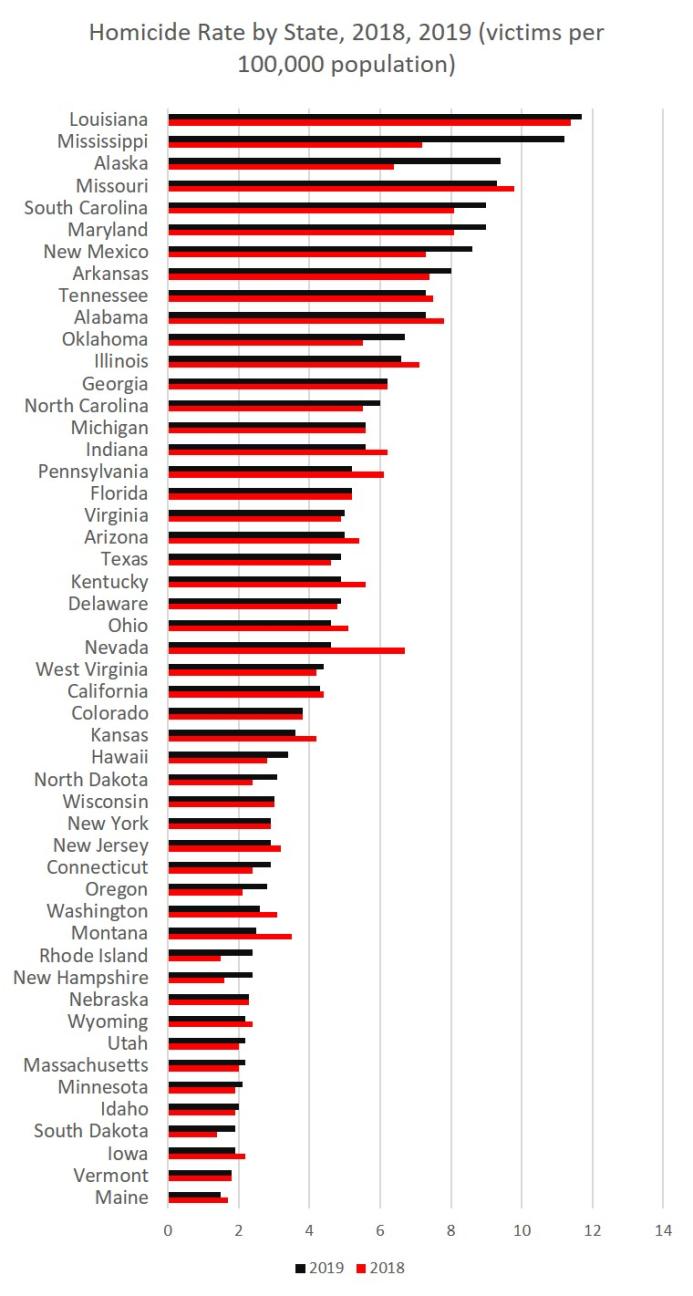

Nonetheless, homicide rates did increase from 2018 to 2019 in twenty-four states. Statewide homicide rates were unchanged in seven states, and rates fell in nineteen states.

As we’ve seen in similar analyses in the past, New England, the Pacific Northwest, and northern parts of the Midwest tend to report the lowest homicide rates. In 2019, the lowest homicide rates were found in Maine, Vermont, South Dakota, and Iowa. The highest rates were found in Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alaska.

What Is the Trend in 2020?

When we begin to look at what data we have for 2020, it looks like the trend is upward. According to the Wall Street Journal the nation’s largest cities are seeing a lot more homicide in 2020 than in recent years:

A sharp rise in homicides this year is hitting large U.S. cities across the country, signaling a new public-safety risk unleashed during the coronavirus pandemic, and amid recession and a national backlash against police tactics.

A Wall Street Journal analysis of crime statistics among the nation’s 50 largest cities found that reported homicides were up 24% so far this year, to 3,612. Shootings and gun violence also rose, even though many other violent crimes such as robbery fell.

Some cities with long-running crime problems saw their numbers rise, including Philadelphia, Detroit and Memphis, Tenn. Chicago, the worst-hit, has tallied more than one of every eight homicides.

Less-violent places have been struck as well, such as Omaha, Neb., and Phoenix. In all, 36 of the 50 cities studied saw homicide rise at double-digit rates, representing all regions of the country.

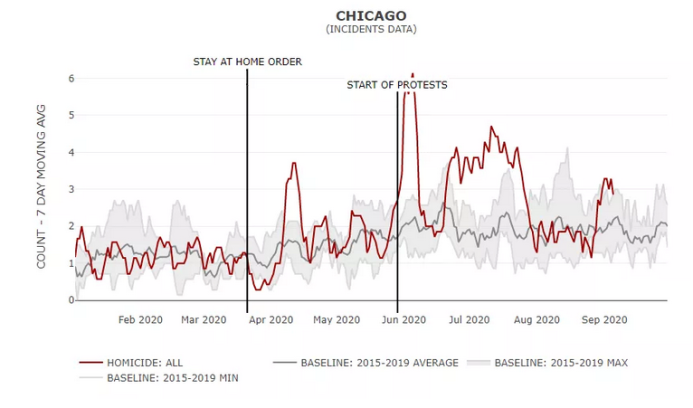

Among these cities, perhaps the most discussed is Chicago, which has indeed shown a sizable increase in 2020 over the previous year. According to The Atlantic, a look at recent homicide data “shows this year’s rate (the red line) rising above the five-year baseline (the gray line and shading) at several points throughout the year.”

Note that homicides began to rise in the wake of the lockdowns but before the riots and protests. Trends similar to Chicago’s don’t show up in all other cities, but the general trend in big cities is clear.

But what is the cause? When it comes to homicide trends, it’s nearly impossible to prove that any one thing is responsible. Criminologists and historians have been debating what drives homicide trends for more than a century.

But given that 2019 was so relatively uneventful in terms of homicide growth, it does appear unlikely that government-imposed stay-at-home orders, business closures, and church closures have played no role at all in rising homicides. Yes, other factors are also at work. The unemployment resulting from business closures—not wholly attributable to forced lockdowns—is likely a factor. It is also likely that the civil unrest connected to antipolice protests and riots have played a part. As suggested in the research of criminologist Randolph Roth, homicides tend to increase as perceptions of the state’s legitimacy go into decline.

However, as the Wall Street Journal notes:

Institutions that keep city communities safe have been destabilized by lockdown and protests against police. Lockdowns and recession also mean tensions are running high and streets have been emptied of eyes and ears on their communities. Some attribute the rise to an increase in gang violence.

Homicides…are up because violent criminals have been emboldened by the sidelining of police, courts, schools, churches and an array of other social institutions by the reckoning with police and the pandemic, say analysts and law-enforcement officials in several cities.

Schools let out young adults in March because of the pandemic and after-school activities largely stopped. Churches and other social institutions were restrained for the sake of social distancing.

“Gangs are built around structure and lack thereof,” said Jeff La Blue, a spokesman for the Fresno police department. “With schools being closed and a lot of different businesses being closed, the people that normally would have been involved in positive structures in their lives aren’t there.”

The Atlantic also suggests a role for the pandemic response among other proposed causes such as rising gun sales and rising unemployment.

A Side Effect of Lockdowns?

When it comes to lockdowns as a source of conflict, the problem lies in the fact that governments have forced the closure of the very institutions which do much to defuse violence within communities. Indeed, the connection between these social institutions and violence has been suggested for decades by sociologists.

Known as “third places,” these institutions play a key role in encouraging peaceful human interactions. As noted by researchers at the Brookings Institution:

Third places have a number of important community-building attributes. Depending on their location, social classes and backgrounds can be “leveled-out” in ways that are unfortunately rare these days, with people feeling they are treated as social equals. Informal conversation is the main activity and most important linking function. One commentator refers to third places as the “living room” of society.

Without these institutions, people living on the edges of criminality are more likely to feel alienated and lacking in community support of any kind. Violence often follows. During the worst of the lockdowns, city residents faced closed schools, closed churches, and closed businesses. As the Journal notes, under these conditions violent gangs may offer a much-needed refuge from government-imposed isolation. Even with stay-at-home orders lifted, governments continue to impose restrictions on social institutions like churches and other meeting places and threaten them with police harassment in the case of noncompliance. Yet these third places cannot simply be shut down—or their services drastically reduced—without creating the potential for greater conflict and antisocial behavior.

It is likely folly to try to pin rising homicides in 2020 on any single cause, but we should not be shocked that a rising homicide rate is accompanying the so-called new normal. After all, the government-imposed shutdowns have done far more than shut down community organizations. They have thrown millions of Americans out of work—with more than 10 million former workers currently collecting unemployment benefits—and they have set the stage for a rising tide of evictions and bankruptcies. History has shown that economic malaise does not necessarily come with rising crime. But unemployment rarely helps matters.