Reviewed by: Rabbi Reuven Chaim Klein

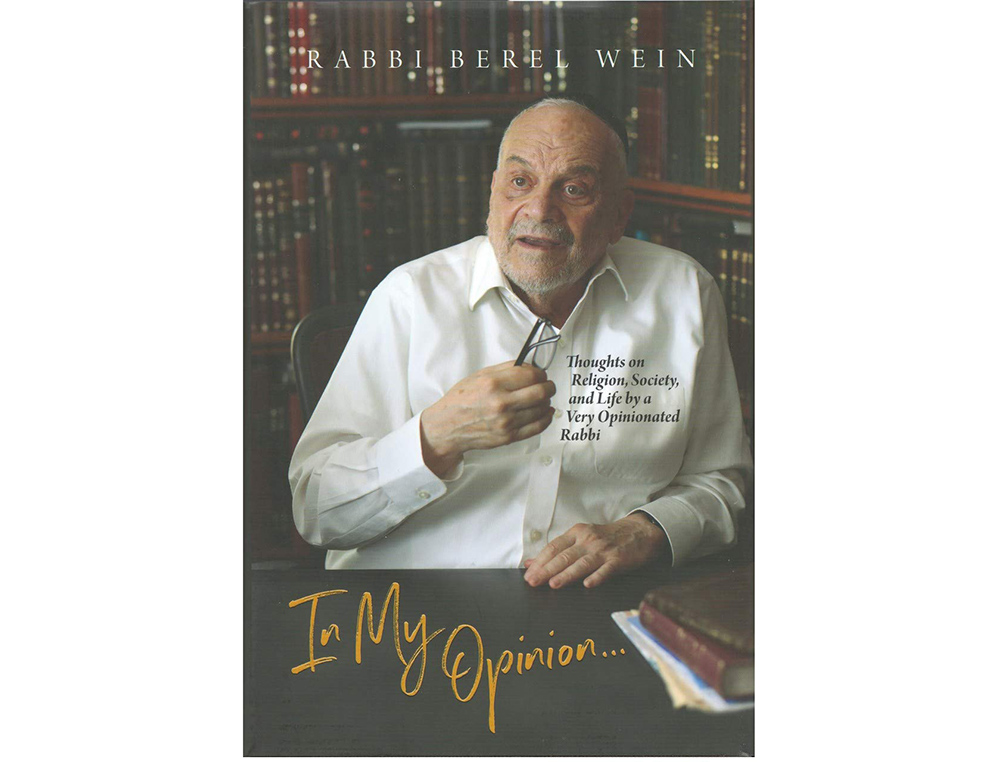

Rabbi Berel Wein has certainly been “around the block” a few times and then some. Throughout his long and varied career, he has worn many hats: lawyer, congregational rabbi, rosh yeshiva, and historian, to which you could also add tour guide, fundraiser, and journalist. In this new book, Rabbi Wein draws from his decades of experiences to offer us tidbits of wisdom and express his learned opinions on a myriad of topics.

This anthology is comprised of about 150 articles that Rabbi Wein wrote, each article running about 2–3 pages. In addition to offering his take on serious issues like current events and the state of Judaism, this book also features Rabbi Wein’s musings on such random topics as Uber, texting, answering machines, Vin Scully, Jewish humor, half-birthdays, and punctuality.

Many of Rabbi Wein’s articles relate personal anecdotes that highlight the foibles of life. These often-humorous observations always carry a message that will help improve the reader’s life, or at the very least will give him a new way of looking at things. These include lessons learned from trying to find a parking spot in the City of Gold, or the magical minyan where ten people always show up, but never the exact same people.

One overarching theme of these essays is the difference between living in Israel and living in the USA. That said, Rabbi Wein’s unabashed love of Eretz Yisroel is readily obvious. All in all, Rabbi Wein remains ardently Zionist, and yet, as a rabbi he remains staunchly religious and devoted to Jewish Tradition.

As can be expected of the man most famous for his books on Jewish History, Rabbi Wein’s essays also draw on historical examples to teach us lessons relevant to the everyday world of politics, morals, business, and world Jewry.

Two important ideas that keep coming up in his articles are his view on anti-Semitism and the need to unite the Jewish People. Rabbi Wein’s articles remind us time and again that — contrary to popular reports — anti-Semitism remains an unvanquished dragon that continues to rear its ugly head from time to time. This is especially true of its latest Israel-bashing incarnation as the movement to boycott Israel. Rabbi Wein views this movement, which is ever so popular in Leftist circles and in American Universities, as but the latest form that age-old anti-Semitism has taken on.

The proposed antidote to many of our woes as a people is the re-unification of the fractured Jewish people by focusing on our similarities, instead of on our differences. As Rabbi Wein reiterates this point in multiple essays, this is especially true within the various groups that comprise Orthodoxy. Rabbi Wein lovingly criticizes any aspect of Jewish Life that he feels needs to be reconsidered. In that sense, neither the Liberals to his left nor the Hareidim to his right are spared the brunt of his criticism. But all of this is done with the understanding that we are one people—even if some of us have glaringly obvious imperfections.

Other recurring themes include the lack of parking in Jerusalem and Rabbi Wein’s inability to change a light bulb.

Some of the articles in this book are devoted to rabbinic personalities, each of whom is important in his own special way. These include the likes of Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz, Rabbi Dovid Silver, and Rabbi Isaac HaLevi Herzog.

The essays in this book are loosely broken up into 10 sections, with each one containing about 15 essays. These include a section on holidays and other special days in the Jewish Calendar, a section on lessons learned from history, and a section on inspiration gleaned from everyday experiences.

As an editor, I would say that this book could have been better organized by theme or topic, and at least should have an index. I also noticed the inconsistent style of the names of Biblical characters, whether they were Anglicized (Abraham, David, Moses) or transliterated from Hebrew (Yocheved, Yitftach, and Yishai).

Like many of Rabbi Wein’s other works, one can criticize this book for its lack of sources. Even when Rabbi Wein quotes explicit passages from the Bible or the Talmud, he never cites his sources. Another point of criticism is that this book tries too hard to please everyone, such that it avoids getting into any real controversy. It also seems that in the quest to avoid creating too much of a stir, Rabbi Wein is sometimes too vague and unclear in his own criticism of others. Because of that, the reader is sometimes left scratching his head pondering to himself, “I wonder what he meant by that.” Of course, Rabbi Wein — a true Ohev Yisroel — is never hyper-critical about fellow Jews, but I felt like sometimes in this book, he launches an attack and then pulls back his punch without even explaining what the attack was. Meaning, he criticizes but in such a vague way that fails to really get his point across.

Throughout the book, Rabbi Wein is not as pessimistic or cynical as he makes himself out to be. Rather, he takes on an optimistic, but pragmatic/realistic view of the world. His self-deprecating humor and false pride are endearing to the reader, and his idiomatic way of writing allows his sincerity to shine forth. When reading this book, you can almost hear the words coming off the page in Rabbi Wein’s signature Chicago drawl with the dramatic pauses that punctuate his world-famous lectures. I, for one, really enjoyed this book. It was entertaining, informative, and inspirational.