It’s worth ending up in a re-education camp for

By: Danusha Goska

(Continued from last week)

Like Night at the Museum viewers, I was too focused on GWTW’s plot, and its writing, to pay attention to the racism, which my mind skipped over.

I read GWTW for the second time by candlelight, on a bed made of raw lumber planks and thin cotton batting. I was a Peace Corps volunteer in the Himalayas. By that time in my life I had attended Twelve Step meetings, to deal with issues arising from growing up in a home where both fists and alcohol were overused. Twelve Step deprograms codependents. It quashes vocabulary that romanticizes sick behavior, and replaces it with clinical terms. Dad was not a “poet … too good for this world;” he was an “alcoholic.” Your girlfriend is not “intriguingly unpredictable;” she has “bipolar disorder.”

In this Twelve-Step-inspired reading, I realized that Scarlett and Rhett are psychologically unbalanced. They do everything they can to sabotage their relationship. This, to me, was suddenly not a romantic tragedy, but a case for therapeutic, and perhaps pharmaceutical, intervention. I wasn’t alone. In a 2011 blog post, professional therapist Jeannie Campbell outlines why she diagnoses Scarlett as suffering from histrionic personality disorder. Dr. Barton Goldsmith, in a 2020 Psychology Today piece, calls Scarlett and Rhett “the poster children for dysfunctional couples.”

In that second reading, I realized something else. GWTW is a racist book. Mitchell romanticizes the Klan and insults her black characters. In spite of all this, I could not help but think, man, this is one hell of a read. The pages are propulsive and pushed me forward. I thought, you could take an X-Acto knife, and slice out the racist garbage, and be left with a book deserving of the title, “Great American Novel.”

My big sister Antoinette succumbed to a brain tumor in 2015. I had spent my life stepping into footsteps that she had trod first. I inherited her clothes, her toys, and her books. After she died, I decided it was time. I read GWTW again. I read it in the autumn, under a feather quilt she had lent me during a previous cold snap. Once she got her diagnosis, I realized I’d never have to return it.

On this third read, I loved Ashley, again. I wished, in vain, to be as good as Melanie, again. I was repulsed by Rhett and aghast at Scarlett. None of this was new. My mind had time to realize: this book is racist, and you could never snip out its racism with an X-Acto knife.

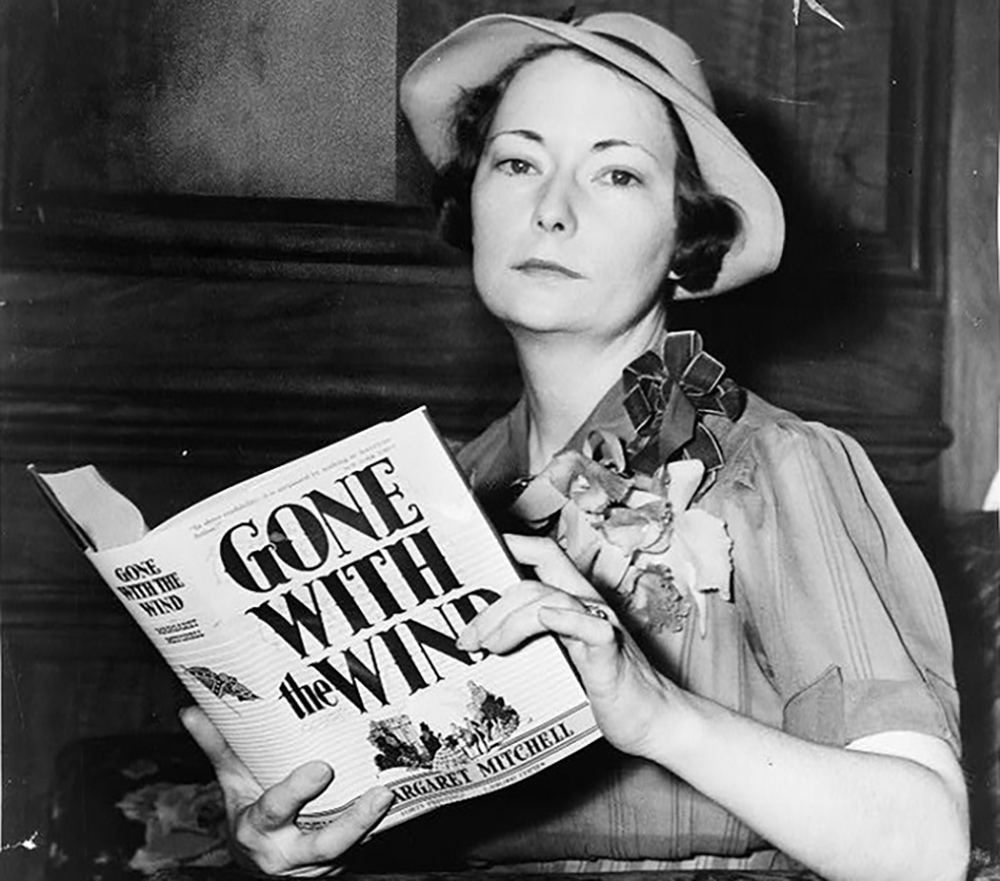

The straw that broke the camel’s back came close to the end. Mammy has loved and nurtured the family for three generations. After Bonnie, Scarlett’s child, dies in an accident, Mitchell writes that Mammy’s “face was puckered in the sad bewilderment of an old ape.” I hated Margaret Mitchell. She betrayed Mammy. I threw the book across the room. I would not allow myself to be defiled by any connection to it. I ranted on Facebook.

A Facebook friend educated me about Mitchell’s philanthropy. I suddenly felt ashamed. Mitchell had done things for black people that I could never come close to doing, yet I was setting myself up as her judge, jury, and executioner.

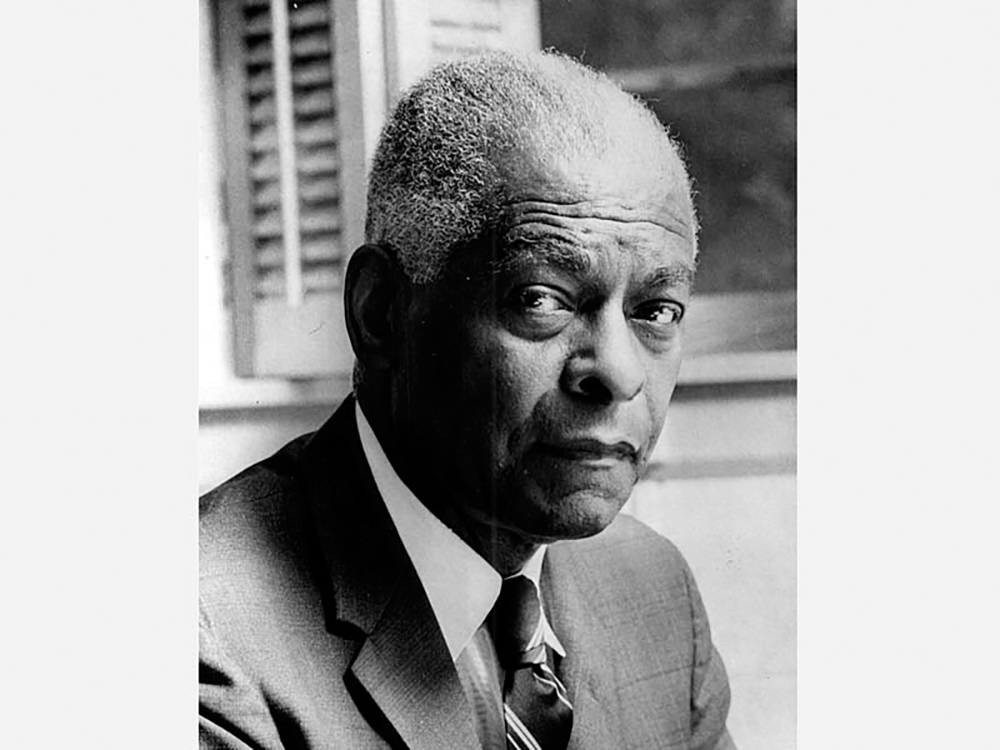

Mitchell formed a friendship with Dr. Benjamin E. Mays, the son of a slave and president of Morehouse College. Mays is “credited with laying the intellectual foundations of the American civil rights movement. Mays taught and mentored many influential activists, including Martin Luther King.” At Mays’ request, Mitchell made significant, anonymous donations. These donations were inspired by her efforts to get adequate health care for her own beloved African American servants. This quest turned her into “a driven visionary who accurately predicted Atlanta’s future as a black metropolis and quietly but fiercely fought racial inequities.” Mitchell’s activism was prematurely cut short when she was fatally injured by a drunk driver. But her family carries on. “In March of 2002, Eugene Mitchell, the nephew of Margaret Mitchell, donated $1.5 million to Morehouse College establishing the Margaret Mitchell Chair in the division of humanities and social sciences. This donation is one of the largest individual gifts in the history of Morehouse College.”

Mitchell carried on a decade-long correspondence with Academy-Award-winner Hattie McDaniel. McDaniel initiated the correspondence, writing to Mitchell to thank her for creating Mammy. She praised Mitchell for the book’s “’authenticity’ that echoed stories of the Old South she’d heard from her own grandmother, and, especially, for creating the character of Mammy and making her ‘such an outstanding personage.’” Later, McDaniel would write, “’in grateful recognition of the many fine things that have come my way since you created in your book the lovable character Mammy which enabled me to gain a measure of success in the field of cinema arts.’” Mitchell wrote to McDaniel, “Every time I see Gone with the Wind (and I have seen it five times) my appreciation of your genius in the part of Mammy has grown … I have felt ungenerous that I have not written you fully about how wonderful I think you were.”

In a key scene, Mammy walks up a flight of stairs toward the room where a grief-stricken Rhett has secluded himself after the death of his child, Bonnie. Mammy explains to Melanie (Olivia De Havilland) the tragedies of the household. Mitchell wrote, “I do not weep easily but now I have wept five times at seeing you and Miss de Havilland go up the long stairs. In fact, it’s become a joke among my friends – but they cry, too!”

This staircase scene has 122,000 hits on YouTube. Post after post under the video praise McDaniel. They call her “brilliant,” “perfect,” “awesome,” “powerful,” “legendary,” “raw and real” “towering,” and “thirty years ahead of the rest of the cast.” “Nothing beats Hattie’s acting.” “Anyone else want to hug Mammy?” “As a person of color, I’m proud of her.” “I’ve watched this scene a hundred times, but it’s still heartbreaking.” “Of all the great scenes from GWTW this one’s my favorite … One of the most deserved supporting Oscars ever awarded.” “I get chills.” “I don’t see how anyone can watch this scene without choking up.” “One of the best acted scenes in all of movie history.” “She was the moral center of the story! I know people criticize her for playing a slave but she stole every scene she was in.” Fan praise for McDaniel goes on and on. Clearly, like the man watching Night at the Museum II and focusing so much on Amy Adams’ attributes that the rest of the movie flies over his head, these fans are so focused on Hattie McDaniel’s’ talent that they cannot focus on the film’s racism.

In the book, amidst all the casual use of derogatory language, Mitchell produces prose that beats with real love. After the war, Yankees come south. Some Yankees say that they would never “trust a darky.” Scarlett is apoplectic. “Not trust a darky,” the paragraph begins. “Scarlett trusted them far more than most white people, certainly more than she trusted any Yankee. There were qualities of loyalty and tirelessness and love in them that no strain could break, no money could buy. She thought … of Mammy coming to Atlanta with her to keep her from doing wrong…But the Yankees didn’t understand these things and would never understand them.”

I understand any African American choosing to reject this love from Margaret Mitchell. It is too interlarded with condescension and racist cant. But no one can deny that what Mitchell expresses in this paragraph is real love, and given what we know of her efforts to help her own black servants, that love was, however flawed, entirely real.

I realized a few more things on my third read of Gone with the Wind. There is a category of people that Mitchell denigrates far more savagely than African Americans. Poor, Southern whites, people Mitchell invariably refers to as “trash,” are, with Yankees, the novel’s monsters.

There are many good blacks in GWTW: Mammy, Dilcey, Pork, Big Sam, to name a few. When a “big, ragged white man” tries to rape Scarlett, it is Big Sam who saves her. The would-be rapist has torn her clothing and her breasts are exposed; Big Sam discreetly averts his eyes. After Sherman, Pork keeps the family fed. Uncle Peter raised orphaned Melanie and Charles Hamilton. Aunt Pittypat is “a grown up child,” “a helpless soul,” who “can’t make up her mind about anything.” Black Uncle Peter treats white Aunt Pittypat like a child, and makes up her mind for her. He is her surrogate spouse.

Yes, these black characters are good because they are supportive of white characters. The book is about Scarlett, and it sees the world through her eyes. But these characters are no less well-rounded than any white characters. They have their own distinct personalities and every one of them defies a white person and gets their own way at least once if not several times when their idea of decorum is violated.

There are no such positive poor white characters in GWTW. The closest Mitchell gets is Will Benteen, a Civil War veteran who marries Careen, Scarlett’s sister. But Will is, in Mitchell’s own excruciatingly caste-conscious worldview, not “trash,” but rather something higher, namely a “cracker.” For more on this distinction, see here.

No. Poor white trash, not black slaves, are the lowest form of life in GWTW. White trash kill Scarlett’s beloved mother, Ellen. White trash sabotage Scarlett’s attempts to recover from the war, by demanding taxes she must prostitute herself to pay. Scarlett, at the sight of poor, white trash daring to set foot on Tara’s sacred earth, feels a “a murderous rage so strong it shook her like the ague.” “All her nerves hummed with hate.” Scarlett defies her Southern belle breeding and spits at the “dirty, tow-headed slut,” this “overdressed, common, nasty piece of poor white trash,” this “trashy wench,” this “lousy poor white.” Worse than Yankees burning Tara over her head, Scarlett knows, would be this: “these low common creatures living in this house.” Indeed, Mitchell lists “contempt for white trash” as a sine qua non of Southern identity. In the hierarchy, slaves are their superior. “The house negroes of the County considered themselves superior to white trash.” No less an authority than Mammy declares that white trash are beyond the reach of charity. “It doan do no good doin’ nuthin’ fer w’ite trash. Dey is de shiflesses, mos’ ungrateful passel of no-counts livin’.”

It’s interesting that The Young Turks, John Ridley, Queen Latifah, and other would-be censors voice no objection to the hatred expressed for poor, white trash in GWTW. The 2020 film Emma enjoys an 87% positive rating on Rotten Tomatoes. As in other Jane Austen adaptations, with the notable exception of Roger Michell’s 1995 take on Persuasion, poor and working class British people, especially servants, are objects, not humans. Here’s the difference: the slave-like servants of Emma are white. A 2020 film treats white servants like objects, and that is okay. This double standard hints at a greater truth: BLM’s obsession with race is a cowardly and hypocritical smokescreen for those who describe themselves as “leftists” and even “Marxists” to avoid talking about class. Queen Latifah, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, and LeBron James can posture as convincing revolutionaries as long as they are bashing GWTW or the police on social and mainstream media. Turn the lens toward the vast gap between their luxurious lifestyles and those of the poor of any race, and the revolutionary mask slips. BLM, “supported by capitalists, is disguising the class divisions that Marxism highlights,” wrote Paddy Hannam.

I realized one more thing when I read the book for the third time: it contains some stunningly sophisticated writing, and flashes of beauty.

“Spring had come early that year, with warm quick rains and sudden frothing of pink peach blossoms and dogwood dappling with white stars the dark river swamp and far-off hills … the bloody glory of the sunset colored the fresh-cut furrows of red Georgia clay to even redder hues. The moist hungry earth, waiting upturned for the cotton seeds, showed pinkish on the sandy tops of furrows, vermilion and scarlet and maroon where shadows lay along the sides of the trenches. The whitewashed brick plantation house seemed an island set in a wild red sea, a sea of spiraling, curving, crescent billows petrified suddenly at the moment when the pink-tipped waves were breaking into surf.”

One of GWTW’s most famous set pieces is Rhett bidding, as at an auction, to buy the right to dance with the recently widowed Scarlett. The scene is meant to be naughty and taboo; the obvious comparison is to a slave auction, or prostitution. It’s also meant to be titillating, and it is.

To be Continued Next Week

Danusha Goska is the author of God through Binoculars: A Hitchhiker at a Monastery