By: Ilana Siyance

On Monday June 22, New York City enters phase 2 of reopening, including outdoor seating for dining, in-store shopping and the reopening of more offices, with roughly 300,000 employees returning to work following the coronavirus shutdown. The city has ambitious plans for contact-tracing program, which will prove critical in curbing the pandemic during the phased reopening. As reported by the NY Times, the city has hired 3,000 disease detectives and case monitors, whose job it is to identify anyone who has come into contact with the hundreds of people who are still testing positive for the virus in the five boroughs of NYC daily. The initiative, however, has gotten off to a troubling start. The program’s initial statistics, which began on June 1, shows that tracers are many times unsuccessful in locating infected people or getting them to release info about their contacts.

Only about 35 percent of NYC’s 5,347 residents who had tested positive or were presumed positive for the coronavirus agreed to give information to tracers about their close contacts during the program’s first two weeks, as per the city’s first statistics release. The responses edged upwards slightly, to 42 percent, during the third week of tracing, said Avery Cohen, a spokeswoman to Mayor Bill de Blasio, on Sunday.

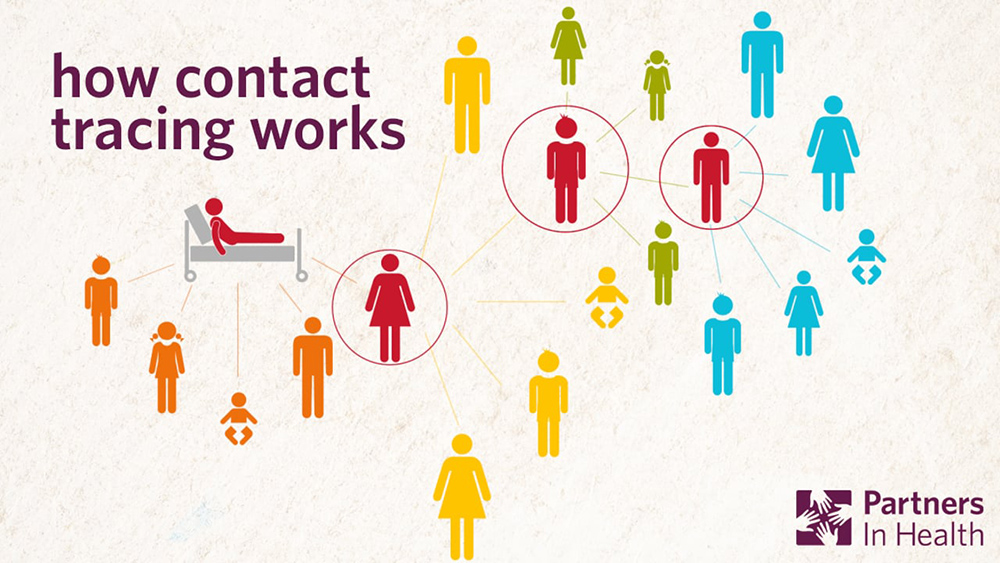

In absence of an available vaccination, the only defenses now available are widespread testing and quarantine for people exposed to COVID-19. Public health officials have also named contact tracing as one more tool the city can use to fight Covid-19. Contact tracing was successfully used before in NYC, with tuberculosis and measles. This time, however, it will be more of a challenge due to the far-reaching span of the disease and its heavy case load.

The preliminary results of New York’s program do not bring an enthusiastic outlook about the possibility of stopping a new surge in cases as the city gears to reopen. Privacy concerns and limited use of technology are yielding a low response rate for the program. Other countries, which are accustomed to more control by the government, have successfully mandated apartment buildings, stores, restaurants and other private businesses to collect visitors’ personal information, easily tracking the spread of the disease. China, South Korea and Germany and other countries require tracking the names and numbers of all attendees at events. Authorities there have also been able to use cell phone data and credit card use to track citizens. Privacy concerns currently prevent U.S. authorities from using such tactics.

Dr. Ted Long, head of New York City’s new Test and Trace Corps, acknowledged that the program was off to a slow start but was optimistic overall. For now, people who tested positive have frequently opted not to share names and info of people they came in contact with, ended the interviews abruptly, or told the tracers they had stayed home and did not see anyone else, declining even to name their immediate family members. Dr. Long said that for now tracers have only tried contacting people who tested positive via telephone, but he is hopeful results will improve when tracers start making house calls in person over the next week or two. “I do think that the program, especially because it is only two weeks old, is doing an outstanding job,” said Long.