By: Bruce Bawer

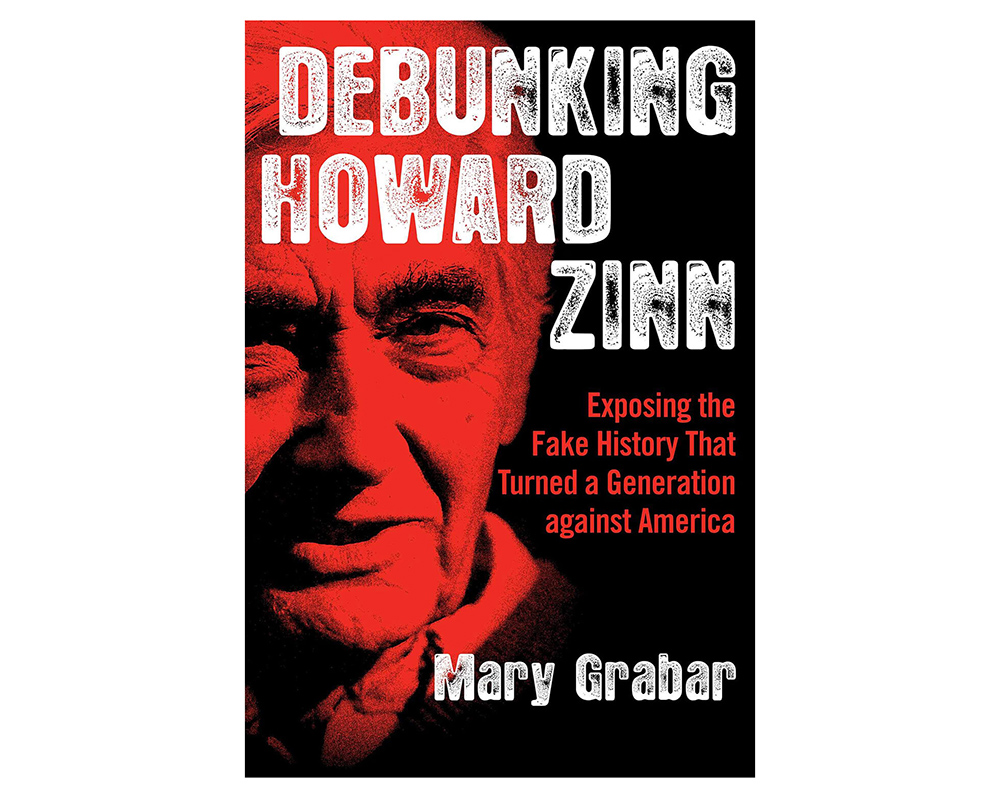

Perhaps the nicest thing you can say about Howard Zinn’s People’s History of the United States is that it shows that even in the era of the Internet a book can continue to have an immense social impact. In Zinn’s case, however, that impact could hardly be more dangerous. Published in 1980, Zinn’s book has for some time been, as Mary Grabar notes in her definitive new study of it, Debunking Howard Zinn, both the bestselling trade history of America and the bestselling American history textbook. When Zinn wrote it, he intended it to provide a skeptical (shall we say) alternative to previous accounts of US history, which Zinn, hardcore America-hater that he was, saw as excessively pro-American. Today, Zinn’s book isn’t just an insidious alternative; it is the reigning book in the field, and its once alternative take on US history has become received wisdom on the establishment left. Not a few of the students who read the book years ago when they were college students, and who fell for Zinn’s take on US history hook, line, and sinker, are now teachers who are using the same book to indoctrinate their own charges.

Many of us have been aware for years of Zinn’s perfidious influence – and have fretted over it in print. But to read Grabar is to realize that the situation is even worse than many of us thought – and to learn things about Zinn that one didn’t know before. One of the things I learned from Grabar is that Matt Damon – who, in the 1997 movie Good Will Hunting (which he co-wrote and starred in) worked in a plug for Zinn’s book that gave it a major boost – grew up with Zinn as a neighbor and was sucked in by People’s History by the age of ten.

Grabar supplies a useful catalog of major historians who, although left-wing themselves, have given Zinn’s book an unambiguous thumbs-down. Eugene Genovese considered it nothing but “incoherent left-wing sloganizing”; Arthur Schlesinger called Zinn “a polemicist, not a historian.” Yet no amount of cogent criticism has dislodged the book from its pedestal. One reason is that teachers who use the book reflexively reject any criticism of it; another is that ignorant mainstream journalists routinely cite it as if it’s a legitimate, reliable work, and a constellation of even more ignorant showbiz Zinn fans, like Damon, have prominently sung its praises. Among the many highly disturbing examples of this misguided promotion was the 2006 publication of the book’s Russian translation – by, believe it or not, the US Embassy in Moscow. Imagine Russians getting their US history from Howard Zinn!

One of the big achievements of Zinn’s book was his utter discrediting of Christopher Columbus. Once regarded as a hero, Columbus is now commonly viewed as having initiated the genocidal destruction of a peaceful paradise. In her first chapter, by going carefully through Zinn’s account of the great navigator, Grabar demonstrates that it is based not on original sources but is heavily dependent on, indeed almost copied straight out of, the work of an earlier Columbus-basher, Hans Koning, who, for ideological reasons, engaged in extremely selective quotation and in wholesale misrepresentation. Ultimately, Grabar shows convincingly that Zinn, in his effort to smear the discoverer of America and to depict American Indians as noble savages, repeatedly ignores historical context, suppresses inconvenient facts, cites exceedingly dubious statistics, and so on. In short, Grabar thoroughly discredits Zinn’s discrediting of the Admiral of the Ocean Sea.

As Zinn progresses beyond Columbus to the British settlement of North America, he routinely deplores relatively minor anti-Indian actions by colonists while defending or ignoring huge, brutal massacres by Indians – whom he insists, against all evidence but in accordance with the historical revisionism of know-nothing Sixties radicals, on portraying as gentle and innocent, indeed, as proto-Communists who lived in hippie-type communes and had no concept of private ownership or gender inequality. In short, Zinn transforms violent warriors into flower children. In one instance, he accuses early Virginia settlers of wanting to “exterminate” local tribes when in fact the latter sought to wipe out the former.

Of course, in the encounters between natives and settlers there were misdeeds on both sides, but Zinn reduces the entire history of colonization as a simple matter of genocidal whites constantly going to war against peace-loving Indians. Nor does Zinn just make virtual saints out of the Indians of the Caribbean and North America; he also whitewashes the Aztecs, Mayans, and Incas. Though he does, surprisingly, mention the Aztecs’ “ritual killing of thousands of people as sacrifices to the gods,” he claims that these bloodthirsty savages nonetheless exhibited “a certain innocence.” Neat trick!

Then there’s Zinn on slavery. In typical fashion, as Grabar notes, he “acknowledges that slavery existed in Africa…but presents it as a kinder, gentler kind of slavery” and is mum on the fact that it predated American slavery by centuries. In his effort to portray slavery, or at least the bad kind of slavery, as distinctively American, Zinn ignores the fact that it was without question opposition to slavery that was distinctively Western, whereas slavery itself had existed in every known African and Asian civilization since the beginning of recorded history.

Far from recognizing the war to emancipate slaves as a uniquely American act of virtue, Zinn laments that the Civil War sought to free slaves rather than to overthrow capitalism, and maintains that blacks were, in any case, no better off after the war than before. He also fails to admit that America’s success in banishing slavery inspired emancipation movements around the Western world, even as he deep-sixes the role of Muslims in the slave trade and the fact that slavery continues to be practiced in the Islamic world.

Zinn manages even to make America’s role in World War II look perfidious. Here, as Grabar says quite rightly, he “hits a new low,” drawing moral equivalence between the US and Nazi Germany, painting Japan as America’s victim, and attributing America’s participation in the war entirely to “imperialist” motives. As for the Cold War era, Zinn dismisses Americans’ fear of Soviet Communism as “hysteria” and describes Americans’ demonstrably legitimate concern about Communist influence in Washington and Hollywood as “paranoid.” He even depicts the Marshall Plan – another unique act of American virtue – as a nefarious effort to prepare “the European capitalist countries for all-out war against the USSR and the People’s Democracies of Eastern Europe.”

Anyway, on it goes. Castro’s Cuba is great; Ho Chi Minh was a hero. Then there’s Grabar’s illuminating account of Zinn’s life. Not only was he almost certainly a card-carrying member of the Communist Party; he also belonged to several CPUSA front groups. Teaching in the late 1950s at the historically black Spelman College, which was “emphatically Christian,” he sought to turn it into a “school for protest.” In 1960, he co-founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, one of the major radical groups of that decade; years later, he co-founded the New Party, which Grabar identifies as “the socialist party that helped Barack Obama win his Illinois Senate seat.” Other groups with which he was associated included ACORN, the Democratic Socialists of America, a “Marxist-Maoist collective” called STORM, and International ANSWER.

This, then, is the man who has shaped the twisted picture of American history – and of America itself –that exists inside the heads of tens of millions of Americans. Grabar’s subtitle is Exposing the Fake History that Turned a Generation against America; my only problem with this subtitle is that in place of “a Generation” she could arguably have said “Generations,” because Zinn’s book, now almost forty years old, has poisoned the minds not only of countless college students today but also of many of their parents.

In her introductory note, Grabar points out that there exist valuable challenges to Zinn, such as A Patriot’s History of the United States (2004) by Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen, which, I have been informed to my delight, is used in conjunction with Zinn in a number of history courses; it would be nice to see Grabar’s own, equally invaluable book find its way onto such curricula. A generation – or generations – of Americans raised on Howard Zinn can result only in an America that turns against its own founding values, in all their nobility, and that follows the likes of Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and, God help us, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez down the path to socialist disaster.

(FrontPage Mag)

Bruce Bawer is the author of “While Europe Slept,” “Surrender,” “The Victims’ Revolution,” and “The Alhambra.” “Islam,” a collection of his essays on Islam, has just been published.