“There was a straight road to Auschwitz,” says Wendy Lower, John K. Roth Professor of History and George R. Roberts Fellow at Claremont McKenna College in California. “When you look back, the Holocaust was inevitable.”

Lower, a historian who spent five years living and researching in Germany, says that while genocides are all a bit different, there are consistent aspects to every mass killing. By leveraging history, she believes, one can almost predict these killings before they start.

Prof. Benedict F. Kiernan, the Whitney Griswold Professor of History, professor of International and Area Studies, and director of the Genocide Studies Program at Yale University, agrees. He tells JNS.org that genocides usually proceed from a combination of causes, long-term and immediate.

First, harsh historical or social conditions create the “fertile political ground that is necessary for emerging genocide perpetrators to be able to recruit supporters and gain the positions of power from which they may implement their criminal policies,” explains Kiernan. He lists warfare, carpet bombing, mass poverty and suppression, catastrophic environmental degradation, and political or economic destabilization as among the long-term conditions from which genocidal extremists may profit the most.

“Without such widespread historical conditions, a genocidal minority would often remain politically isolated or impotent,” says Kiernan.

Second, the extremist leaders share certain characteristics, he notes. These include being obsessed with their own ideological preoccupations, which can range from racism or religious hatred, territorial expansion, romantic agrarianism, and obsession with recreating or rivaling and distant past.

“Not all of these ideological features are harmful on their own, but on their combination is usually disastrous,” Kiernan says.

“You have to have a combination of hateful people and power,” says Peter Hayes, the Theodore Zev Weiss Holocaust Educational Foundation Professor at Northwestern University. Hayes says almost all modern genocides are state-directed, meaning that even the most evil leaders can likely not carry out a full-blown genocide without their country being behind them.

In Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler had that national support. His genocidal platform can be traced as far back as the 1920s, when in Munich, he laid out National Socialist German Workers’ Party’s 25-point plan.

“Among the points was that no Jews can be members of the German race,” notes Lowry. “They put these points on posters and plastered them all over the city.”

Yet it wasn’t until the depression struck in the 1930s that Hitler’s party began to gain steam. Hayes pointed out that in 1928, Hitler’s party only received 2.5 percent of the vote. In 1932, it received 37 percent.

“Hitler was not very successful until there was an intervening factor in the sense of a major economic catastrophe. … All these regimes and genocides begin in a kind of vocabulary of cleaning, a magical thinking that goes into all of them, that they will make their countries great again by stamping out the forces of evil within them,” says Hayes. “It takes an extreme crisis for people to be willing to buy such nonsense.”

In Germany, the Jews became the scapegoat.

“The old proverb is that anti-Semitism rises and falls in inverse relationship to the stock market,” Hayes quips. “No one likes to blame themselves.”

The portents of genocide became increasingly clear in the late 1930s, when the German leadership had a shift in language. In speeches and newspaper articles, Hayes says the Nazis began to use a word they had never used before: annihilation. Before then, the Nazis referred to the “removal” of the Jewish people. “Annihilation” was different.

Then, there was Kristallnacht in November 1938.

“This was the first real act of physical violence against the Jews—their property and their bodies,” Lowry says.

Only a few years later, the Germans made a decision to shoot at Jews as their armies moved into the Soviet Union. It started with the shooting of men and boys in July 1941. By August 1941, they were shooting Jewish women and children, too—“any Jews in the path of their armies,” says Hayes.

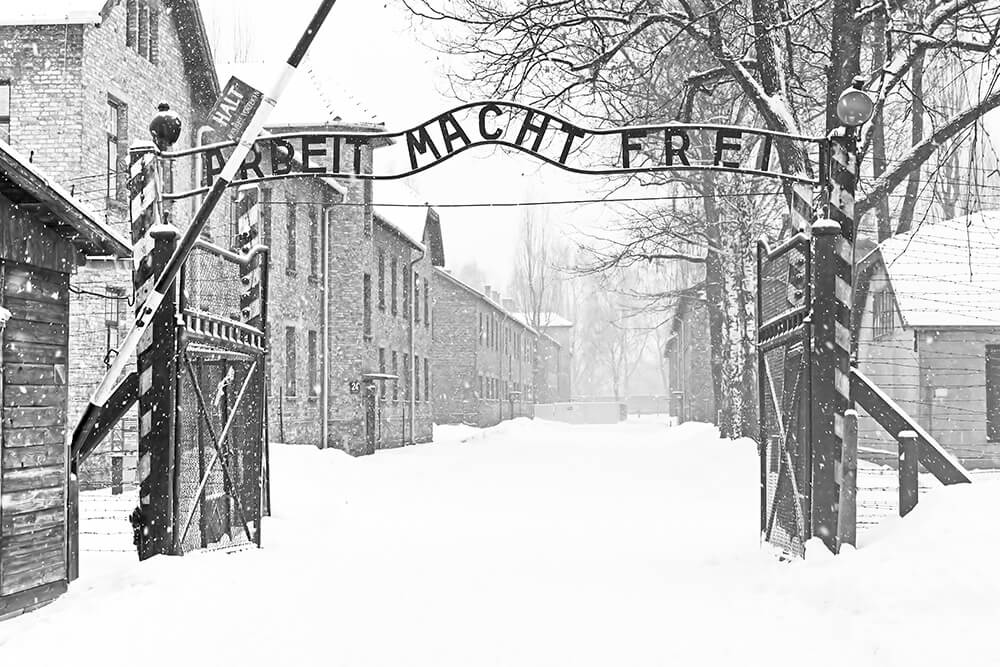

That same year, the first zyklone-b gas chamber was constructed—and tested.

“There were key turning points where fire bells should have gone off—and sometimes they did,” says Hayes, but the Jews had little ability to protect themselves or in many cases to leave due to immigration restrictions and simply being outgunned.

The Holocaust might have been the first example of this systematic type of genocide. But it was not—and likely will not—be the last, Hayes believes. Today, he says, we are obligated to learn from the past.

Moving forward

Education is essential, says Hayes, explaining that one should be able to recognize the difference between extremist activity or political parties and the potential for genocide. In France, for example, while there has been a rise in terrorism against Jews, the state is on the side of the people being attacked.

“The majority population is more angered by the Muslim attacks on the Jews than feeling threatened by the Jews,” Hayes says.

In Hungry, the situation is different.

“Hungry is a borderline case that should be watched,” says Hayes. “Hungry, as a state, is not so protective [of its Jews] and is on the verge of the tipping the other way.”

Hayes also says that Russia has all the combined warning signs for genocide, including national humiliation since 1989, an increasingly difficult economic situation, and extensive anti-Semitism that “might find another outlet.”

“The greatest defense of recurrence of a holocaust is knowledge of the Holocaust,” Hayes says.

What can prevent a contemporary genocide?

“Once a group of people is recognized as vulnerable to genocidal operations, it has to be a priority to those who have the means to provide a safe haven, to get these people out of harm’s way and prevent that loss of life,” says Lowry. “We failed during the 1930s by not providing enough places of refuge. … We have to be more watchful today.”

Hayes says, “The best defense is the defense of liberal principles: the rule of law, treating all people fairly and opposition to theocracy. To stop genocide, these are things one has to defend.”

SIDEBAR: TIMELINE TO GENOCIDE

In hindsight, what events were pivotal in the igniting of the Holocaust?

Feb. 24, 1920: National Socialist German Workers’ Party publicly unveils 25-point Plan, including language that no Jew can be a member of the German race

1930s: Increase in anti-Semitic legislation; anti-Semitism begins to be realized through powers of the state

July 1932: German elections show a 34.4 percent increase in popular support of the Nazi party

Nov. 1938: German officials shift language from “removal” to “annihilation” when referring to Jews

Nov. 9-10. 1938: Kristallnacht, Nazis in Germany torched synagogues; vandalized Jewish homes, schools, and businesses; and killed close to 100 Jews

Fall 1939: First carbon monoxide gas chamber tested in Belzec extermination camp

July 1941: German army adopts policy of shooting Jews as it enters new territory in war

Nov. 1941: Nazis discover use of zyklone-b for use in gassing; experiment in Auschwitz extermination camp

(JNS.org)