His first inklings of the immediacy of Nazi atrocities took place in a neighborhood bakery, in 1956, where the four-year-old Bobby Rosen spotted the tattoo on the forearm of a woman working the counter and coaxed a whispered explanation from his mother. This opens an awareness of the ubiquity of such signs in his neighborhood, and why “A day never passed when I didn’t hear somebody express an opinion about the Nazis—usually my father,” a World War II veteran who was particularly infuriated by the sight of German-designed cars. “Yeah, we all hated the Nazis,” Rosen continues, “and if anybody didn’t, he kept his fool mouth shut about it.”

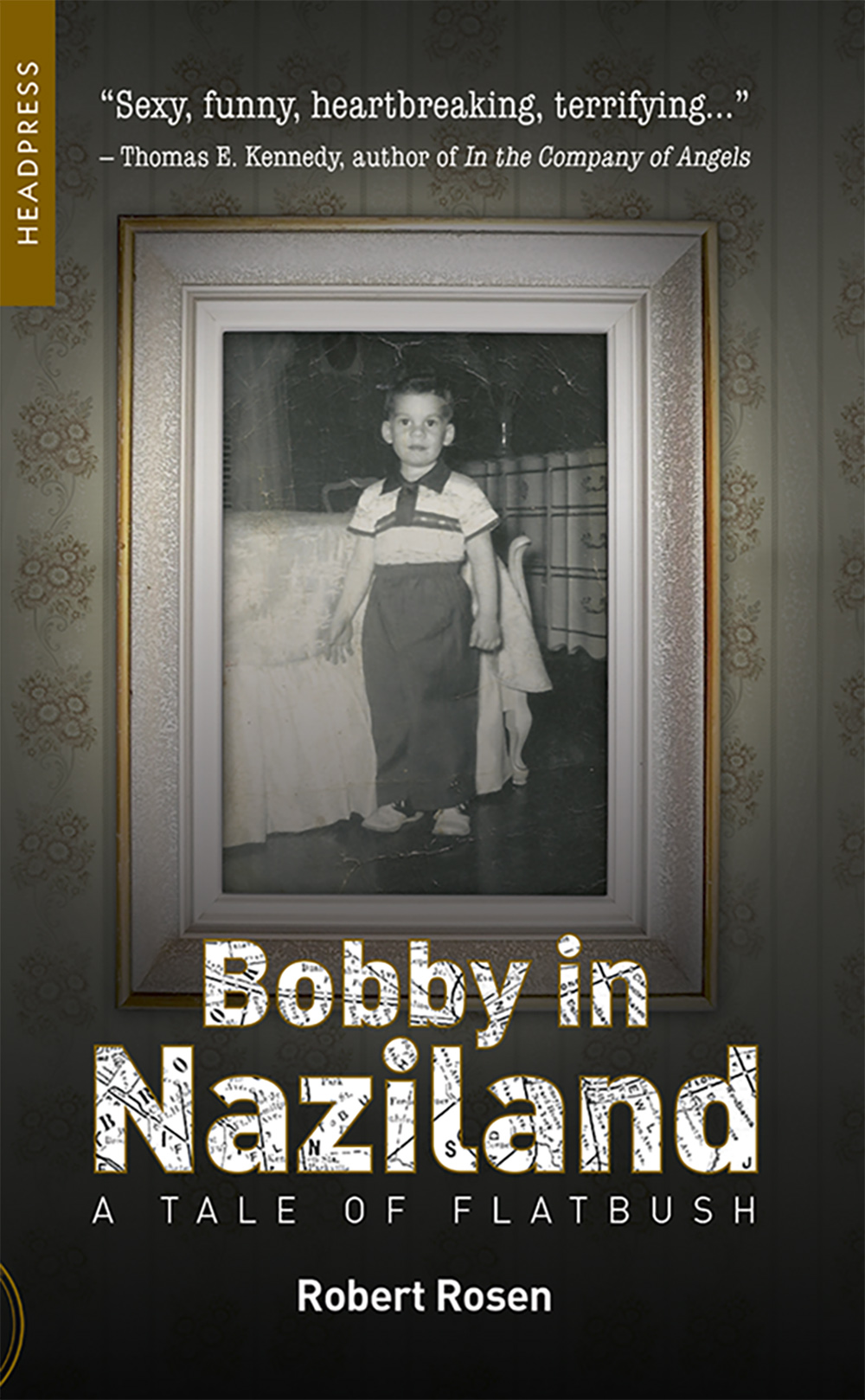

Rosen describes his boyhood in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn in his new memoir Bobby in Naziland (Headpress). This book follows the best-selling Nowhere Man, an account John Lennon’s final days.

Bobby in Naziland takes an episodic stroll through a Jewish neighborhood that seemed stuck in its own kind of timelessness, colored by the multi-directional progression of prejudices reported throughout the book. Anyone who is German is, of course, a target, which for Rosen included his building’s super, Mr. Kruger (“My father called him ‘that damn Kraut’”). “We also routinely beat the shit out of his blond and suspiciously Aryan-looking twin sons … who were my age.”

But there also were Catholics to despise, and Poles and Puerto Ricans. “It was garden-variety bigotry, inane and vicious at the same time.” What Tom Lehrer parodied in his song “National Brotherhood Week” played out for real in Flatbush, where “everyone … I knew hated black people—Jew and goyim alike.” Although racial integration of the Brooklyn Dodgers made it seem as if the borough “were some kind of racially harmonious mecca,” in truth it was bad enough that the 1965 Voting Rights Act had to be applied to Brooklyn as well as the former Confederacy.

We meet the author as a belligerent, foul-mouthed child, fighting with kids in the neighborhood. Kids like the three Alesio brothers. “I don’t know why the sight of them made me crazy. It just did.” His stretch of Brooklyn’s East 17th Street is defined by the families who lived nearby, a variety that he soon learned included an all-encompassing other: the goyim, a term he learned from his parents and grandparents.

It was a term intended to define people like his downstairs neighbor Brian Riley, who suffered physical abuse at the hands of his alcoholic stepfather. As Rosen’s mother explained, the goyim “drink, and then they come home and beat their kids. Aren’t you glad we’re not like that?”

The book’s very readable twenty chapters have a journalist’s precision and a humorist’s facility with language, all put to excellent use in building a compelling sense of the complicated nature of family and neighborhood. “Whatever was happening in Flatbush in the mid-1950s to the mid-1960s … was rich material that demanded further exploration.” After writing down what he remembered, Rosen had 400 pages of material to distill. And “what jumped out at me were Nazis—they were everywhere.”

The young author finds glory in his father’s World War II keepsakes, and, with Third Reich escapees reported on the loose, even contemplates joining the Mossad to search them out. Thus the 1960 capture of Adolf Eichmann was a matter of huge excitement in the neighborhood. What complicates the triumph in retrospect is a result of Rosen’s later research, when he discovered that the man who fingered Eichmann, a onetime Dachau political prisoner named Lothar Hermann, was himself arrested and tortured by the Mossad when they decided, against all evidence, that he was Josef Mengele—and that Israel finally paid him the $10,000 Eichmann-capture reward a dozen years after that capture. To Rosen, that part of the story “changes the very essence of what everybody thought they knew about how Israeli intelligence agents had managed to snatch Adolf Eichmann off a Buenos Aires street.”

William Styron was resident in a Flatbush rooming house in 1949, which provided the setting for Sophie’s Choice. The novel examines consequences of the Holocaust, specifically its effect on post-war Flatbush where, notes Rosen, “Sophie could have been the fictional incarnation of any number of my neighbors.” But his fascination with all things Nazi-related also drew him into a secret reading of William Shirer’s Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, with its lurid accounts of torturous abuse. “Oh, I’ll become numb to it all in a couple of years,” writes Rosen, “and soon enough the very notion of genocidal slaughter will cease to appall me.”

Rosen’s father owned and operated a candy store near his home, which provides the setting for many of the memoir’s scenes. Such as the time Duke Snider, a legendary Brooklyn Dodger, stopped by for what he’d heard were “the best egg creams on Church Avenue.” And there are Rosen’s own stints there as a soda jerk, which allowed him to develop a journalist’s skill at unobtrusively eavesdropping.

As a boy growing up in the early 1960s, he observed signal events like Roger Maris’s home-run streak and the progression of the space missions, which galvanized his family and friends. The death of Pope John XXIII, in June 1963, drew little neighborhood attention. But the assassination of President Kennedy, five months later, changed everything. As Rosen puts it, “The Wall began to crumble.” National mourning was stoked by an aggressive media. “It seemed that every magazine that went on sale at my father’s candy store—Life, Look, Time, Newsweek, The Saturday Evening Post, and even Playboy—had something about the Kennedy assassination on the cover.” It was the first of two events that finally breached the neighborhood’s isolation, finished by the arrival of the Beatles.

Bobby in Naziland portrays the neighborhood during that particular decade with the characterizations and insight of a good novel, although at times it seems a little too dispassionate as the adult Robert reviews the antics of young Bobby with what must be elusive objectiveness. But it really is the neighborhood that’s the star of the story. You don’t have to be Jewish—or a Brooklynite—to be enchanted by this book. But it’s going to take you even further home if you are.

—B. A. Nilsson is a freelance writer who has been covering literature, the arts, and food for a variety of publications for more than thirty years.